|

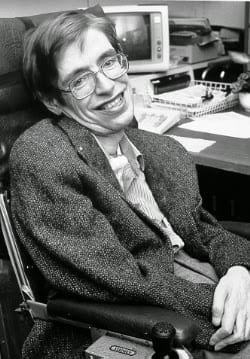

| Stephen Hawking. Photo by NASA |

I’ve been thinking a lot about communication lately. I just finished reading Ghost Boy by Martin Pistorius. It’s the story of Martin, who succumbed to a mystery disease when he was a young boy that put him into a coma for two years. When he “awoke,” he was unable to speak or move any part of his body other than his eyes and some minimal movements of one hand. It took years before someone was able to assess him for brain damage and fit him with a computer device that enabled him to communicate with the world and everyone was shocked at how much he was aware of and understood during the time he was mute and paralyzed.

I have to say, the book wasn’t my favorite, literarily-speaking, but it did spark a lot of thought processes in my head. And ultimately, it led to me watching The Theory of Everything last Friday night. I have loved Stephen Hawking’s brain since I first read Black Holes and Baby Universes for fun in high school. (Yes, I was that nerd). I went on to read “A Brief History of Time” and was completely hooked. His story was different, in that people knew he was brilliant before he began struggling with the symptoms of ALS and could no longer speak or take care of himself, but I was still fascinated by how heavily verbal communication weighs in our assessment of each other as human beings.

I remember when my grandmother was rendered mute by Alzheimer’s disease. Although she had been increasingly confused prior to that time, it was still confusing to me whether or not she understood the lion’s share of what was going on around her. I recall thinking that I would go crazy if I were trapped inside my own head and body, unable to respond or make my needs known.

As a young mother, I recognized my infant’s frustrated cries as just that – a desperate longing to tell me what she wanted and to have some control over her world. Fortunately for her, normal developmental progression let her gradually gain that control. But until she could, I had to change my response to her by listening in a different way, paying attention to her body language and context, the time of day and where her eyes moved. I had to trust that she was doing her best to communicate with me and it was on me to slow down, change my expectations, decipher the clues. When I came from a place of love and genuine desire to know, while it was often challenging and crazy-making, I was able to be more patient.

Some of the stories Martin told about how he was treated by caregivers in various care homes were horrifying. The lack of humanity he was shown simply because he was unable to speak or move his body the way he wanted to made me sad. And it made me think about how often we expect others to communicate with us in the ways we are accustomed to, instead of thinking outside the box. Fortunately, there are those out there who are committed to finding ways to help people like Martin and Stephen Hawking express themselves. As for me, the next time I encounter someone who doesn’t communicate exactly like I do, I hope I’ll have the presence of heart to slow down and find another way to listen.