M.C. Escher knew it.

The Dalai Lama knows it.

Timber Hawkeye talked about it. He puts it this way:

“The opposite of what you know is also true.”

Not, ‘the opposite of what you know is true, but also true.

It was rather an arresting comment. If there had been anyone in the room whose attention was drifting, that sentence brought it back.

“The opposite of what you know is also true.”

I think the most important word in the sentence is ‘know.’ Because so often we fool ourselves into thinking that what we know is absolute. Finite. Provable. Truth with an uppercase ‘T.’

Timber expanded on the notion by giving examples. He saw a TED talk by Derek Sivers, who talked about traveling in Japan and asking for an address so he could find a particular place. He was given the name of a block. He asked for the name of the street.

“The streets don’t have names. They are simply the empty space between blocks. The blocks have names.”

He was confused. Clearly there was some language barrier. The person giving him directions asked, “What is the name of the block you live on?”

His reply: “The blocks don’t have names. The streets have names. The blocks are simply the empty spaces between streets.”

See?

He offered another example from the same TED talk. In remote, rural China, each small village has its own doctor. Every morning, the doctor makes his rounds of the houses in the village, collecting coins from a box hung near the front door of each house. If he comes to a house where the box is empty, he knows that someone inside is sick and his services are needed. You see, in this model, the doctor is supported by the entire village for keeping them healthy. He is not paid when treating them for an illness and, thus, is given an incentive to prevent everyone in his village from getting sick.

“The opposite of what you know is also true.”

Since hearing this phrase and digesting the examples, I have seen it in action. I was reading an article about a documentary film that followed homeless teens in Seattle and came across the story of a young girl who left home after being molested by a family member. She talked about how filthy her mother’s house was, with rotting food and dirty laundry strewn throughout, and what a relief it was to live under a bridge in the city because it was actually cleaner than her home. She found places to wash and brush her teeth and worked hard to keep herself presentable and live according to her standards of cleanliness. It was only a few weeks before she realized, however, that being young and female on the streets makes you incredibly vulnerable and that not washing or paying attention to how she smelled was the best way to prevent herself from being raped.

The words keep kicking around in my head, finding me in the quietest times and in the loudest. Much like stubbing my toe, I keep bumping up against my own ideas of what I “know” and challenging them. I suppose that, before this, I would have seen a filthy young girl on the street and assumed she was either mentally ill or been disgusted by her – maybe both – instead of thinking about what it must be like to go against your own convictions in order to simply survive.

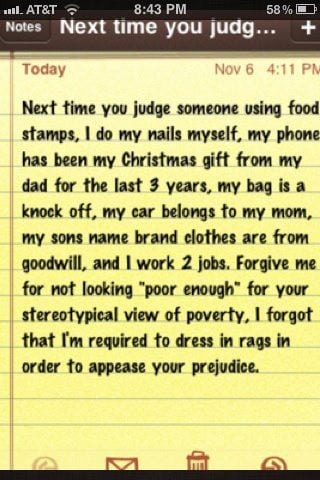

Yesterday, I came across this photo on Facebook:

At the original site, there were comments ranging from “right on” to nasty, blaming, shaming diatribes from people who “pulled themselves out of poverty without any social services.” My first instinct was to rise to the defense of the person who posted this photo, and then I stopped to consider what I “know.”

I know what my experiences are. That is all I can know. I don’t have to know everyone else’s reality or even strive to. All I have to do is realize that there are limits to my knowledge and that, while it feels terribly, starkly real, it is not “Truth.” Except for me. And so I cannot go out into the world trying to spread “Truth.” I can only go out into the world with compassion and a desire to understand and expand my own experience and knowledge and not make any judgments or actions based on my own brand of knowing.

Because the opposite of what I know is ALSO true.