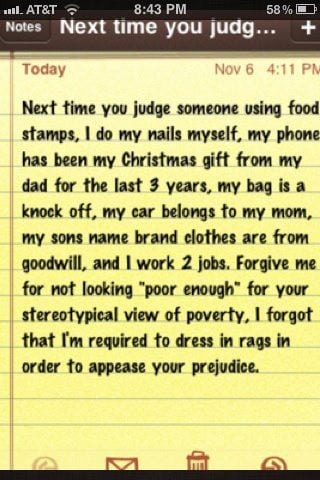

Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Klamath Falls, Oregon

My spiritual journey has been, well, a journey so far in my life. I’m certain that on the day I was born, nobody expected me to have a spiritual journey. They expected to baptize me in the Catholic Church, raise me in the Catholic Church, and bury me after a lifetime spent in the Catholic Church. I guess, technically, that’s a journey, but it stays pretty well within the same track, or at least I (and my mother) always thought so.

Until I was eight or so, this worked out pretty well. Enter: divorce. We were fairly rigorous Catholics, going to Mass on Wednesday nights and Sunday mornings, taking confession (at least my parents did) and signing us kids up for catechism classes. The path was preordained. Until my folks split up. And the Church politely asked us not to return. Bad example for the rest of the parishioners and all that.

Until that point I hadn’t questioned much about religion or faith. I didn’t know anyone who didn’t go to church on Sunday and I frankly loved the ritual of church, if not the time spent there on sunny mornings. I loved dipping my fingers in to the font of holy water at the entrance to the church and crossing myself like I saw the adults do. I loved genuflecting before entering a pew and memorizing the steps that went along with different prayers – when to sit down, kneel and stand. I loved the music and the stained glass and knowing when to say a solemn, “Amen” or “and also with you.”

After my folks got divorced, Dad seemed to have no issue not going back to that church and sometimes, especially in the summer, took us to his version of church on Sunday mornings – a short hike near Crater Lake or up Mt. McLoughlin with a few quiet moments to stop and enjoy the view while he prayed and thanked God for our time together. I much preferred that kind of church to the ones my mother tried out thanks to recommendations from friends – a new one every weekend we spent with her.

By the time I was in high school I had thoroughly catalogued the hypocrisy I saw in my own family and friends Monday through Saturday and decided that church and religion seemed ridiculous. I still liked the music, but there was little ritual in any of the churches we attended and I cringed at some of the messages of punishment and anger I heard over and over again. I was relieved when I got a job at a local resort that held a huge Sunday brunch because I could beg off of church – we needed the money more than Mom wanted to admit.

I had also become increasingly interested in science and liked the ordered, logical view of the human body as a machine. I renounced religion of any kind and decided I was an atheist. I didn’t see any reason to think there was an afterlife and was openly disdainful of anyone who seemed to be simply tolerating their time on the planet until they could get to some paradise. I was determined to create my own paradise now – hedge my bets because I would be really pissed off if I discovered there was no Heaven after I had waited decades to get there.

Philosophy classes in college further solidified this view for me. I took a comparative religion class and was astonished to discover how many really strange theories there were about different leaders and prophets and how malleable morality could be depending on which one you adhered to. Couple that with the more complex science classes I was taking and I was definitely convinced that humans were basically machines. Yes, we have emotions, but I was certain there were discoverable physiological processes that could account for those. This view did not diminish the wonder of nature for me a bit – in fact it increased it more than anything. The notion that there were so many variations in this mechanistic view of the world – that DNA could be expressed in so many different ways from a strawberry to a hyena to a human with Down’s Syndrome – that was truly miraculous to me. And, ultimately, explainable with enough scientific knowledge. Who needed religion?

And then Buddhism hit me. It was not one of the religious views I had learned about in college and I knew very little about it, but about six years ago I started writing book reviews for Elevate Difference and was assigned a few Buddhist texts. I also began taking yoga classes and heard more about Buddhist beliefs there. The entire idea that a spiritual world view could exist without worshipping some deity or other was fascinating. The tenets of peace and equanimity and love appealed to me greatly – especially in their inclusion of every other sentient being on the planet. I was determined to learn more.

Today, I guess I would say that my spirituality is more deeply rooted in Buddhism than any other world view. And while I still love the idea that the human body is a machine, and live that reality every day by trying to feed it well and rest it appropriately and work all of its parts with some regularity, my notion of it has expanded to include a spiritual component. I don’t know exactly how I would describe it – a soul? some invisible connection between all sentient beings? I’m not sure. But I heard an explanation on NPR (where else?) a few weeks ago that has slowly been settling in to my bones. I can’t for the life of me remember what program or who said it or even what the context of the conversation was, but the question was whether animals have souls or not. The answer came by way of analogy: If you have a computer that is broken and you take it apart to discover why, you can fix it and put it back together and it will work (assuming you knew at you were doing) the exact same way it did before. If your pet (or your sister-in-law or your favorite dogwood tree) is ailing and you take it apart piece by piece and put it back together exactly the way it ought to go, it won’t come back to life. There is something more, something extra, something intangible that we sentient beings have that defies mechanical explanation.

In my atheist days, this explanation would have thrown me. I am certain I would not have known what to do with it, given that I had an entirely mechanistic view of humanity. You die and you’re dust. Period. Nothing else.

Today, I’m not so sure. Some might say it’s because I’m getting older and facing my own mortality, but I would like to think that one day I’ll be back in some other form to finish this journey of mine. If I get to choose, I’d like to be a very pampered indoor cat who spends its days chasing bugs and sleeping in the sun patch at the end of the bed.