In fact, we’ve needed to talk for a long time now, and we’ve been avoiding it. I’m looking at white women when I say that and I hope you’re hearing me. I hope you don’t flinch, or if you do, I hope you stay on your feet and don’t turn away. It is well past time, and it’s our responsibility to stay with this until we start to get it.

I want to call out some behaviors and tactics I see us all engaging in that are harmful and keep us from doing what we need to do right now, and I hope you stay with me.

1. Performative Wringing of Our Hands – It is fine to feel upset. It’s good, actually, but it’s not enough. It isn’t enough to post on social media, to change our profile pictures by adding a “Black Lives Matter” frame around it (full disclosure: I did that when Ahmaud Arbery was killed). It isn’t enough to tell everyone how upset we are, to cry and post petitions on Facebook and reTweet memes. We have to stop making our feelings the center of the discussion. It is great to amplify the voices of folks of color who are tweeting and posting without adding our own commentary unless it serves to call our fellow white women in to a deeper conversation. Telling everyone you’re going to “Run for Ahmaud” is about you, it’s not about him and his family and the systemic violence and brutality black folks in this country face every day. Run, by all means, and use it as a way to talk to your other white friends who run – ask them whether they ever go out for a run and worry that they will be shot by a white man under false pretenses, ask them if they worry about their children being shot by a white man under false pretenses, talk about why that is. Have those conversations often without telling your black friends about them and expecting praise. Have those conversations daily without expecting some sort of pat on the back or prize for doing it from anyone.

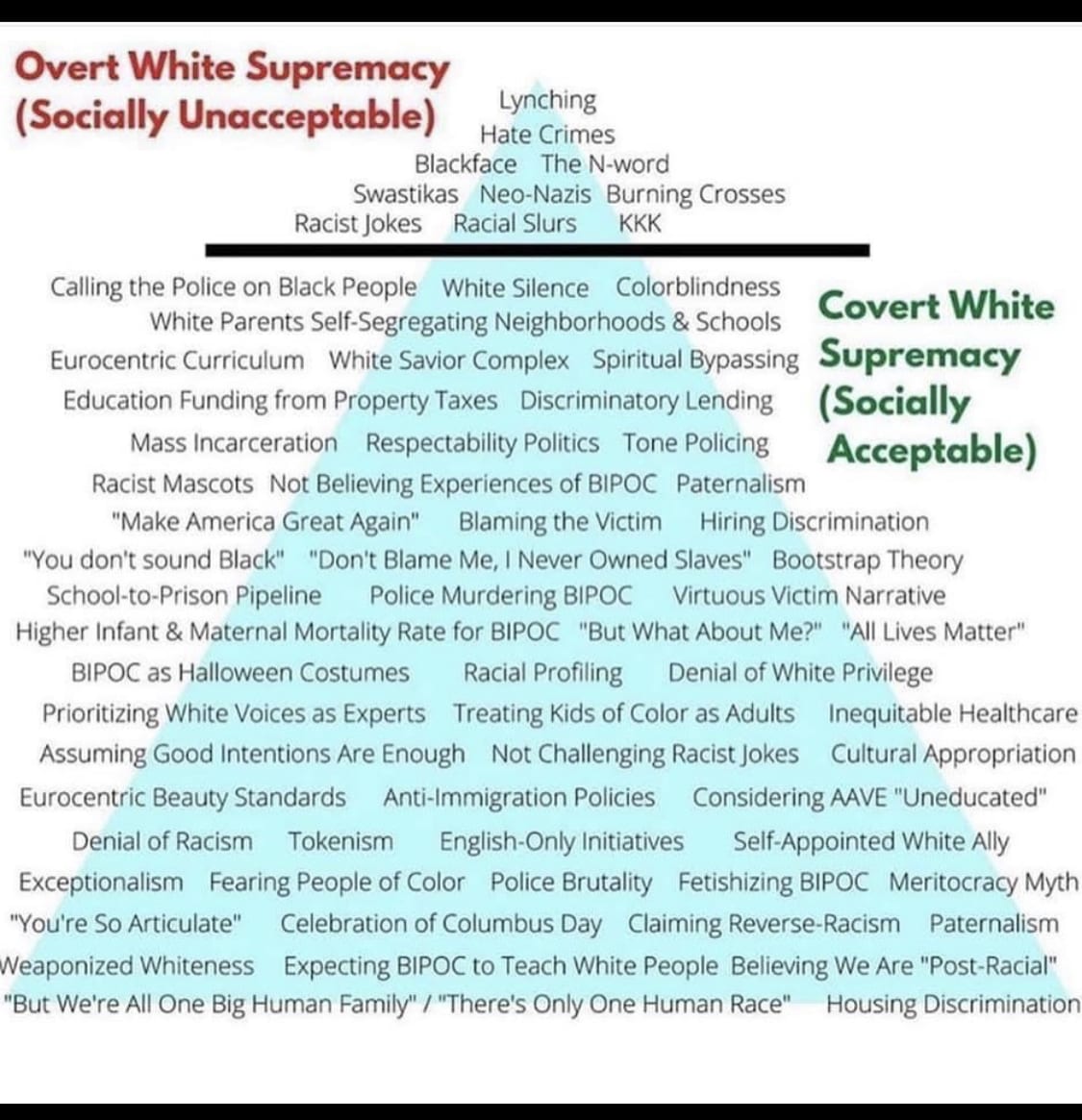

2. Asking “What Can I Do, Though?” – This is a cop-out (excuse the pun). It is an excuse to flinch and turn away. And we’ve been doing it for far too long. We can’t “fix” this. We can’t sign petitions and lament on social media and register a bunch of voters to work our way out of this. It. Won’t. Happen. We need to get past our desire to “fix” something, because that centers us, once again, in all our White Saviorism. This notion that if we can’t take some specific action, we might as well not do anything is an excuse to give up before we’ve started. The black folks I’ve spoken to have encouraged me to help them hold their grief, to listen listen listen to them and validate their lived experience, to light candles and pray in whatever form that takes. They’ve also encouraged me to have lots and lots of conversations with my white friends, to help them unpack the bedrock beliefs and hidden biases we all have, to practice sitting with the discomfort of knowing we are complicit because we benefit from the systems that vilify and kill them every day in a million different ways. Until we acknowledge that we aren’t “lucky” or “blessed” but benefitting from privilege and colonialism and capitalism, we can’t begin to really move forward to dismantle those systems. We white folks want to sign a petition, march one time, post all over social media and call it done. Black folks I’ve spoken to know that this will take continued, diligent effort, and many many conversations. Elevating their voices, stepping back where we can and letting black folks lead, and talking among ourselves so that we can build communities of accountable white folks is vitally important and far less satisfying than “checking a box”. That said, there are absolutely specific things we can do – marching and petitioning are important, paying cash bail for black protestors who’ve been arrested is vitally important, calling our elected officials every single day to let them know that we won’t stand for police brutality, that we need to reform the justice system, and that officers need to be held accountable for their actions are important. But we will never make substantive changes unless and until we learn to really sit with the discomfort of talking to our white friends about how we are and continue to be complicit.

3. Expecting Change to Come Quickly and With Minimal Effort – This is a big one. The fatigue is real. But anyone who has ever fought for social change in a substantive way knows that, while there is always a tipping point, that point in time only comes after years and years of hard, honest work. That “it’s not happening fast enough” notion comes from our unwillingness to sit with the discomfort. We want to “fix” it so we don’t have to keep witnessing it, and what my black friends are saying is that it’s incredibly important for us to keep witnessing, to help them hold the grief and rage of it because we’ve been denying it for so long. We can’t fix it by ourselves, and if we think we can, we are buying in to the White Saviorism that will end up doing harm. I honestly believe that we white folks need to unpack our shit, get really clear on where we’ve been wrong, where we’ve been complicit, and then step aside and let the folks who are dying lead us. I don’t think we can be silent, but we need to be loudest with our white friends and family. And that is going to take time and a great deal of work.

4. Blaming Systems – Expecting the systems to get us out of this one (voting in new leaders, a gradual culture shift in policing, greater education in our schools about racism and white supremacy) is complacency. It is laziness. It is us being unwilling to swim in the waters we have helped create that are literally destroying communities of black and brown people. Blaming systems (government, fascism, “our country”) serves only to deflect responsibility from the people who run these systems and those (like us white women) who benefit from them. We need to stay in discomfort, acknowledge the ways in which we have held up these principles and systems, not wallow in shame, and work through our own fears about what we might lose if black and brown people are treated with full humanity and equality in this country.

This is our work. It is hard and necessary. And we can do hard things if we do them together. It is our responsibility as white women of privilege to do it. Telling others loudly and proudly that we want change without being willing to dive deeply in to these really hard conversations is disingenuous. It means we don’t really want change, or that we want it to happen in spite of us. But the truth is, it can’t happen without us. This isn’t about judgment or vilifying anyone. It is about steeling ourselves for what we’ll find, knowing that whatever happens, it won’t kill us, and trusting that we have the strength and power to do this work. I hope you’ll join me. It’s well past time.