It shouldn’t surprise me anymore, but it still does – how the ripple effects of the decisions of rich, European landowning men continue to fuck things up for all of us.

Warning: small history lesson incoming – but be aware that, in school, history was my least favorite subject, so I will do my best to be concise.

Have you heard of the Valladolid Debate? While you can read up on it at Wikipedia, and learn that it was basically a set of arguments between Spanish colonizers and Christian theologians that took place in the 1500s to decide whether or not it was ok to basically enslave and torture Native Americans, ultimately it was the decision that was handed down at the conclusion of the debates that continues to make life suck in colonized places of the world.

You will likely NOT be shocked to hear that both sides claim to have won the debate (turns out rich men in power have never been able to imagine a world in which they don’t prevail), but the damage was done. The idea that natives were “closer to nature” than they were to being human stuck in the minds of European colonizers – and extended to women as well, thanks to their ability to give birth and their monthly menses, and it justified many atrocious, horrendous acts against them for centuries to come. It was around this time that the philosopher René Descartes was making his ideas about humans as machines popular, and thus, the beginning of ideas about medicine and “humanity” were shaped as well.

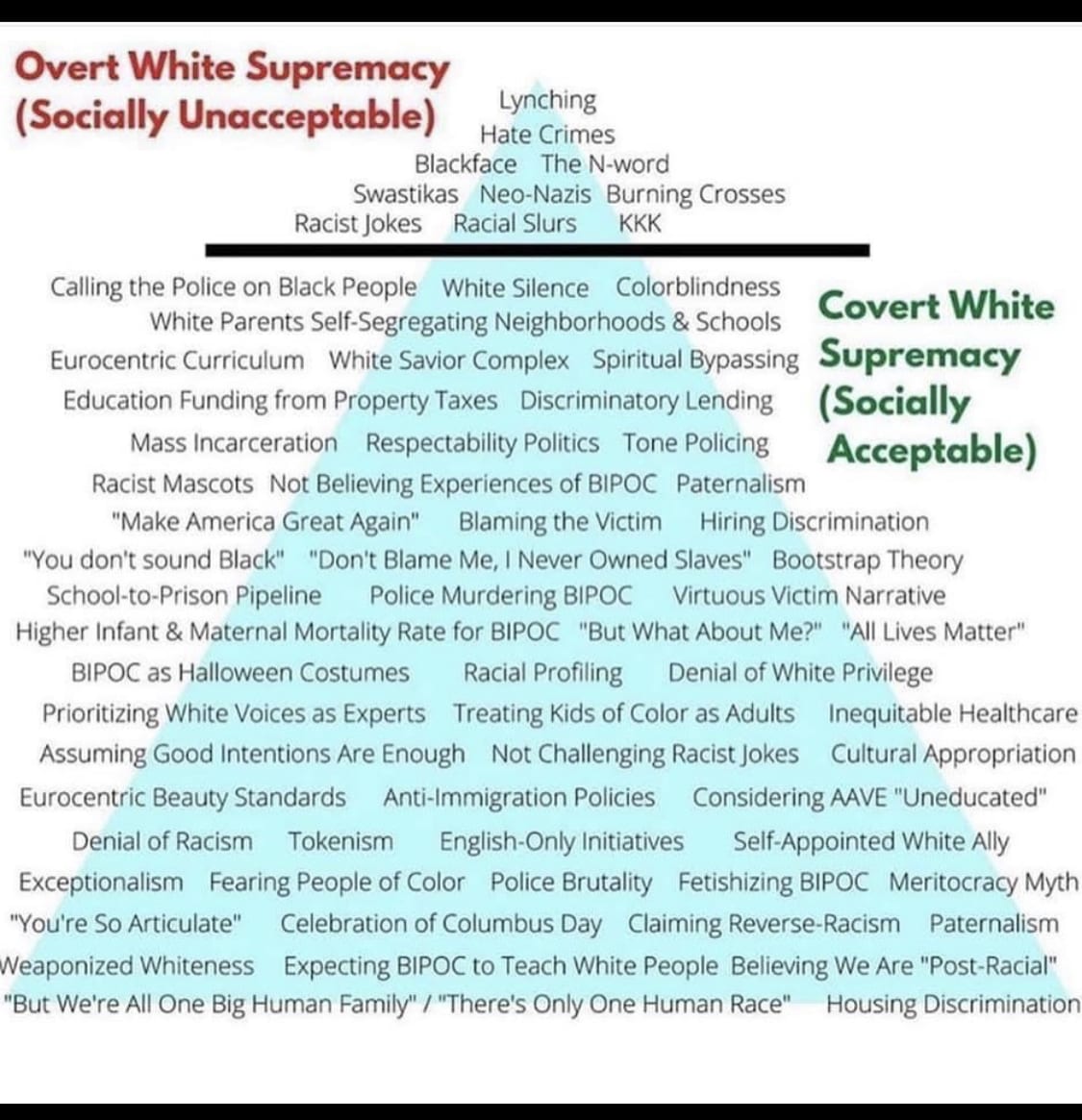

It is not a leap to say that the value judgment that was made was that things that were closer to nature (and thus, much harder to tame or control) were less than human, while things that could be described as mechanistic and predictable were better. Humans have always looked for safety and security, so this isn’t terribly surprising, but the fact that those ideas led to the curbing of human rights (well, for pretty much everyone other than rich, White, landowning men) as well as the creation of things that helped control our world and continually sever us from our connections to nature has done a great deal of harm.

How many of our systems and structures are breaking down and causing active harm now simply because they are built on the notion that humans ought to be more machine-like and less “natural”? How many of these systems rely on the binary system of good/bad, right/wrong, controlled/chaotic rather than understanding and acknowledging the complexity of what it means to be a biological creature?

Our school system was created with the idea that we all learn in the same way (or at least we should), but the increasing understanding of neurodiversity is straining that notion, and keeping us from being as creative and vibrant as we could be.

Our medical system is made up of specialists who compartmentalize knowledge and treat symptoms far more than treating the whole human and acknowledging the interconnectedness of not only all of the systems within our bodies, but the way they interact with food, water, the environment, and our cultural norms and social contracts. We parse out teeth for dental care and emotional health for mental health care and eyes for vision care as though they don’t exist within the larger whole.

Our system of currency is not about understanding what resources human beings truly need to thrive, but about zeros and ones and accumulation of wealth in a very strict, controlled way that ignores the fact that this puts stress on all of the other systems because perpetual growth of one system cannot happen without exhausting the resources of all the other systems.

I could go on, but you get the idea.

The continued push to pretend that human beings are separate and apart from nature, that it is our job to have dominion over it in one way or another, to completely disregard the fact that we are biological creatures is harming us all. Often, in my Grief & Rage Workshops I will ask participants to check in and discern whether they are letting their mind or their body run the pace of their days. It is incredibly rare for folks to say that they let their body be in charge of the pace – not only because it is nearly impossible to do so in this capitalist world, but because we have been taught, conditioned to believe that our minds have supremacy over our bodies. But letting your mind continually be in charge of your pace is like driving your car for weeks on end without ever checking to see if there is gas or oil in the engine, air in the tires. Eventually, it will break down and fall apart. Pretending that we are not biological creatures doesn’t mean we are automatically machines. Just because it would be easier to live that way doesn’t mean it’s true.

How different would our lives be if the outcome of the Valladolid debate had been that being “closer to nature” was actually the preferred value judgment? What if these “scholars” had determined that those who lived in harmony with the land were doing something right by noticing and responding to the complexity of their relationship to their surroundings, by working together and paying attention to cycles and rhythms of day and night, seasons of the year, only taking as much as they needed and not trying to control or dominate just because they could? And how do we turn that around now?