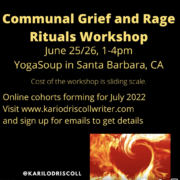

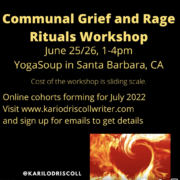

If you can’t make the in-person, please scroll to the bottom of the home page and sign up for email notifications so I can tell you when the online cohorts are ready to go in July.

If you can’t make the in-person, please scroll to the bottom of the home page and sign up for email notifications so I can tell you when the online cohorts are ready to go in July.

January has been a long month. Seriously. I know I’m not the only one saying that, and that the last two years have honestly been such a time warp in general, but it is only the 22nd day of the month and I honestly feel as though I’ve lived several lifetimes this year so far.

Last Monday I woke up with a nagging headache. Not debilitating, but pretty uncomfortable. I’m no stranger to headaches in general, since I have a very finicky neck that doesn’t allow me to sleep in certain positions or do particular tasks that most people wouldn’t think twice about. Probably once a month, I end up with a pretty gnarly headache that requires a trip to my phenomenal chiropractor to fix (she shakes her head and says, “what have you done?” in a very gentle, caring manner that reminds me I am in good good hands and puts everything back where it is supposed to be and sends me on my way). So, honestly, that’s what I figured this was. I made my way through the day with Advil and the hope that it would resolve on its own.

But around midnight on Monday/Tuesday, I started to notice that I was thrashing about in bed quite a bit and that is really unusual for me. It only took a minute before I realized I was spiking a fever – this was chills, and the headache had kicked up a notch. I knew pretty much right away that this was Covid. I stuck it out until dawn and then took my temperature to confirm, texted a friend who I knew had access to home tests, and waited.

It was a rough four days. That headache was brutal. Not the worst one I’ve ever had, but definitely second in line. I couldn’t watch tv or read or really look at much of anything. I just laid on the couch staring into space and hoping it would abate sooner rather than later. Somewhere in the back of my mind, I remembered that when I first moved here last May, this was the scenario I feared most – that I’d get sick while living on my own and not be able to really take care of myself or the dogs. I’m here to say that, like most fears I’ve ever had in my life, this one didn’t play out the way my amygdala warned me it would.

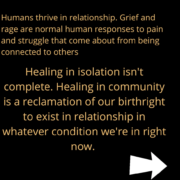

I had friends near and far texting me all day long, checking in, offering help of any kind. The friend with the home tests also brought soup, Gatorade, bottles of water, cold medicine from her own stash, and Meyer lemons from her tree. Other new local friends offered food delivery, dog walks, and just general moral support. One of my neighbors, having spotted a friend dropping off supplies at the front door, texted one night to say her husband had just made a beautiful homemade dinner – could they fix me a plate and leave it at the door for me?

I was brought to tears with each and every one of these offers, and I accepted it all (well, not the dog-walking – my dogs would no more leave me behind at the house and go walk with someone else than they would chew their own leg off). Blissfully, the headache subsided by Day 3 and I remember lying on the couch, imagining my poor, stressed brain inside my skull, sending it waves of soothing light to recover. Every little thing I did prompted a two-hour nap. The last time I was this exhausted was after giving birth to Erin and that was only because I caught the flu while I was in the hospital so I brought her home and spent the first week battling a fever and trying to recover from a 40-hour labor.

I’m still recovering, but finally not sleeping 16-18 hours a day. I am able to do a few things here and there and then lie down for a bit to rest. There is some acute sense that if I don’t go slowly, there is a real danger of setting myself back, and I can’t help but wonder how people with children at home or elders to care for or lots of work to do that needs to be done manage this. It honestly brings me to tears to think about having to make a meal for someone else or go to a job feeling such extreme fatigue. I wish we lived in a world where we believed each other when we say we need rest, where we made sure to provide space and the necessities for that to happen. I recognize my massive privilege in this – that I was able to be cared for from afar by friends and family, that I am able to put off my work obligations as long as I need to, that I have a roof over my head and a soft bed in which to recuperate. I wish that for everyone.

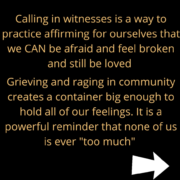

It is so interesting that one of the first things people ask is “where did you get it” and then “were you vaccinated?” I am reminded that we have done a really good job of framing this pandemic in the same way we frame nearly everything in this culture – in terms of personal responsibility. I know that those two questions are some attempt to insulate ourselves – if we think we can crack the code, we can avoid getting sick. But I also know there is some judgment there because that’s what we’ve been taught. If you just didn’t do X, you wouldn’t be struggling with Y. I am so much more taken by the folks who ask “how can I support you” and “what do you need?” There is a radical form of community that can be created just by asking these simple questions and I am here to tell you, it feels amazing to be the recipient of it. On Thursday night, when I was so astonished by how absolutely tired a person could feel after sleeping most of the day, my phone pinged with an incoming email. As I read something from a friend expressing her deep care for me and her fervent wish that I recover quickly and thoroughly, I spent a few minutes going back through my day and replaying all of the text messages I’d gotten from a dozen or more friends and family members, checking in, offering help, saying they were sending love, and I made the conscious decision to hold that in my head and heart as the last thoughts before sleep – the notion that I was held in deep care and love by so many people from literally all over the planet. It was magic.

I’m now a week in and my sense of taste and smell is coming and going unpredictably, I struggle to catch my breath when walking the dogs on our normal, flat, 20-minute route through the neighborhood, and I still occasionally sit down after doing something mundane like folding a load of laundry and feel a powerful need for a nap. My sleep is the sleep of the dead – deep, strange dreams and waking up feels like swimming up from the depths of the ocean, but I am grateful for the freedom to sleep when I need to and for friends and family who text or call or email to check in and let me know they’re rooting for me. That is medicine for my soul.

What is it about having that breeds wanting?

Last week my oldest, who I hadn’t seen for nearly six months, managed to get four days off of work in a row and she flew out for a visit and a rest. Seeing her reunite with her sister and her best friend, waking up and walking out of my room to see her sound asleep in the guest room, having coffee with her in the morning – it was exquisite. And I found myself longing, thinking, more of this, please! I also found myself dreading the moment she got on a plane to return to her life thousands of miles away.

It is exhausting perching on the point of now, toes crammed together on the peak, looking at the down slope of what could be (and often, what I wish for) on one side and on the other, looking at the down slope of what has been and what might have been different. My mind races forward and back like a dog chasing seagulls on the beach, imagining, hoping, wishing, lamenting, preparing for the end of what is.

It is in those moments when I can dial back my perception to the now, imagine the tip of this present time flattening out, stretching to let my feet stand firm, toes spread wide, that I begin to find gratitude and let go of longing. I lose the fear of what could have been or what might be and practice – shaky but resolved – appreciating what is. In those times, I am able to remember to notice the joy of being with beloveds, pay attention to the laughter and the way the light falls and the smell of jasmine on our walk through the neighborhood. My mind tugs at me, wanting to find a way to prolong it, reproduce it, prevent it from ever stopping. It is surprising how insistent that impulse is, how quickly it can make me stand back up on tiptoe and lose my balance.

I am trying to remember that our bodies can only ever be in the Now, while our minds are almost always in the past or the future. And while being in my body can sometimes feel incredibly scary, with its pockets of fear and unprocessed pain, in the present moment, more often than not, I am safe, and I can find a measure of joy.

But this empty-nester thing is for real. I am 49 years old and I have never lived alone. I went from living with my sister and mom to a college dorm with a roommate, to an apartment shared with my brother, to living with my future-husband. I was married for 23 years and even after the divorce, I had my girls with me most of the time. The occasional weekend when they were away at their dad’s house didn’t prepare me for the long stretches of time alone. I am continually shocked at how rarely I go to the grocery store, prepare a full meal, talk to another human being (I talk to the dogs a lot). Everything is brand new right now and it takes effort to flatten that pinpoint Now so that I can stand, feet flat on the Earth, in full connection with this moment and remember that, at least in this second, the future is none of my business.

My uncle said something last night that struck me and it fits in with so much of what I’ve been chewing on mentally. He said, “we aren’t a society, we are an economy. We aren’t citizens, we’re workers.” He said it ironically, as he and two of his sisters and I were railing at what passes for health care in the United States – at how we commoditized it and made it a business instead of a way to meet the basic needs of human beings in our communities.

And then this morning, Nicci sent me a Marco Polo (seriously, folks, I’m addicted to this platform and the way we can record videos for just one other person and instead of a dynamic, ongoing conversation, we have to really listen to the other person in earnest, hear their thoughts and ideas, and sit with them before formulating a response) that, among other things, made me think about my parents’ generation and how they were taught (indoctrinated?) to believe that they had to be in service to something bigger, and how that was noble, and desirable, and that martyring one’s self to that larger thing (Capitalism and “Democracy”) was not only expected but lauded.

But, hear me out: a collective, a community, is only as healthy as its individual parts, and my parents were taught that they ought to eschew their own health and well-being in order to be of service to something else. And if they did a good enough job, they’d get a pat on the head and a pension and Capitalism and Democracy would live on through their efforts. And so my dad went to Vietnam and fought for “Democracy” and came home broken broken broken. And my mom quit teaching and stayed home to raise children and held on to her marriage with this broken broken broken man in service to her religion, her society (raising “good” children and all that), her country (as if). I know for a fact they both had dreams and passions and I also know that they sublimated those things out of a sense of duty. I know that they weren’t able to ask the question, “What would make me happy?” From time to time, when either of them was particularly tortured and unhappy, they were able to ask, “what would make this suffering stop?” – but they never saw their own well-being as something that would serve the collective.

I once heard Gloria Steinem say “if you want to have something at the end of your journey, you have to have it all along the way.” She went on to explain that if we’re looking for joy or a sense of purpose, we have to have experienced it as we go, or else we’ll never be able to recognize it or appreciate it once we get “there,” wherever “there” is (for the record, I don’t think there is a “there” there). But at least one entire generation of people were taught (indoctrinated?) that what they wanted in the moment wasn’t important. They could plan for retirement, to have “joy” and an opportunity to relax and indulge your passions and interests at that point, but until that time, you had to be of service.

But a healthy collective is made up of healthy individuals. A peaceful collective is made up of peaceful individuals. The thing we are working for has to also benefit us in some tangible, meaningful way. I’m sure my parents both believed that Capitalism and Democracy would benefit them, but only inasmuch as it prevented other horrible things from affecting them – things like Communism and Socialism, lawlessness and anarchy and amorality. But I can tell you that, while my parents lived fairly comfortable, middle-class lives and they remained safe from whatever demons were out there, for the most part, neither of them got to enjoy their retirement. My dad died at 65 from an aggressive form of cancer (brought on by, you guessed it – his time in Vietnam) and my mom was forced into retirement by Alzheimer’s. Neither of them got the chance to travel or pursue a passion or reap the benefits of their efforts on behalf of That Larger Thing.

So what if we flip this on its head? What if we teach a new generation of young people that grounding themselves in who they are, what they want, where their natural talents lie, and serving that is serving the collective? What if we teach them that, the stronger and more peaceful and purposeful they are, the more they are able to connect to others with clarity and compassion? And that those connections are what actually serve the collective? What if we don’t place the emphasis on some external thing that needs them to be/act/work a certain way, but instead look at what they need in order to act from a place of security and abundance? What if we make sure that they have what they need (food, shelter, access to the education they choose, health care, a supportive community and family) and know know know that this is what the foundation of our strong collective resides on?

The kind of service my parents’ generation was built on required more individuals to constantly replenish the ones that burned out. It was this hollow shell of Capitalism and Democracy with worker bees propping it up and it ran on volume so that when some of the bees got sick, others could rush in and replace them. But building our communities from the inside out, ensuring that each individual who is part of it is healthy and has what they need, means that we have a solid core from which to draw our collective well-being. While I spent most of my life saying I wanted to be “of service” and believing that that was an incredibly noble thing, I now think it is important for us to examine exactly what it is we think we’re “in service” to. If what we really want to be is part of a community of care that honors all of us, then our work lies in making sure we are clear on our purpose and passion, that we are able to ask for what we need when we need it and offer our support to those whose needs can be met by us. Taking care of ourselves and being able to recognize our talents and gifts as well as knowing what joy looks and feels like along the way is how we serve the collective.

![]()

Thanks for visiting my site. I’m driven by the exploration of human connection and how we can better reconnect to ourselves, our families, and our communities. Aside from my books, I hope you’ll check out my blog, and some of my other writing to find more perspectives and tools.

This site like most every site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

OKLearn MoreWe use cookies to let us know when you visit this website, how you interact with it, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more and for the opportunity to change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on the website and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will impact how our site functions. You have the option to block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. Please be aware that this means every time you visit this site, you will be prompted to accept or refuse cookies.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

Privacy Policy