I am reading my first book by bell hooks. I have read quotes of hers before and come across people who think she is absolutely brilliant and yet, I have never once picked up a book by her. Until now. And to be honest, I don’t even really remember what made me pick up “All About Love: New Visions,” but it is quickly becoming a tome to set next to the likes of David Whyte’s “The Three Marriages” and anything by Brene Brown to read over and over again. I have taken so many pages of notes I’m running out of space in my notebook and I am only about 70% of the way through it.

hooks’ meditations on every kind of love from friendships to family to intimate, romantic relationships to self-love are so simple and profound that I am stunned again and again. And, as I often do, I find myself stopping mid-page to muse about the ways in which her philosophy pertains to different aspects of my life and pop culture. The fact that her thoughts feel so incredibly universal to me is one reason why I suspect I will be able to read this book many times and find some new perspective during each and every reading.

She begins by defining love in a way I’ve never heard it spoken about before and, yet, it feels absolutely right to me. She uses M. Scott Peck’s definition, the will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth, as a springboard, and adds, “To truly love we must learn to mix various ingredients – care, affection, recognition, respect, commitment, and trust, as well as honest and open communication.”

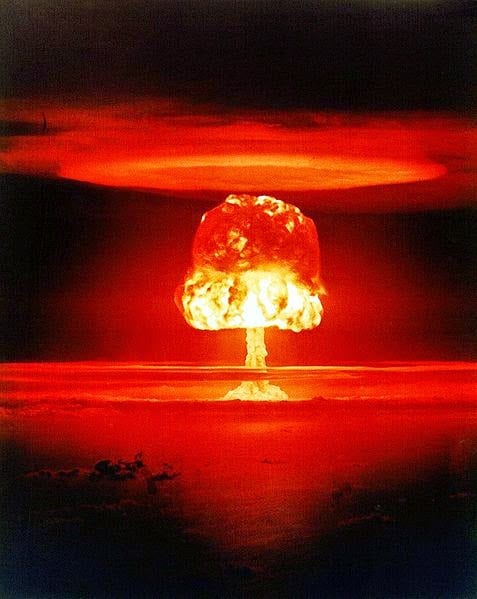

She has chapters on every imaginable application of love but in light of what is happening in the Middle East right now, I am particularly struck by her chapters on community and what she calls a “love ethic.”

I have been called hopelessly idealistic and a dreamer most of my life. I own it. And so, in that spirit, I began thinking about what the world would look like if we embraced the notion of a love ethic, cultures rooted in mutual respect and acknowledgment instead of materialism and consumerism and money and power. In this kind of society, it would be absolutely necessary to address our fears and take daily leaps of faith. In this kind of society, we would be required to forego the possibility of having everything we want in order for everyone to have some of what they want. In our current model, we are encouraged to think constantly about what we as individuals want which sets up this endless cycle of desiring and attaining and assessing and desiring more. We are always comparing what we have with what we don’t have, what we have with what others have, and we will always come up short. In our current model, where possessions equal success equal power, we are tricked into thinking that more stuff will make us happier and we dehumanize other people who get in the way of us having more stuff.

When I think about the daily violence happening in Gaza and Syria, I see a cycle of fear and entitlement. I see groups of people desperate to have exactly what they think they need and willing to go to any length to get it. I see militaries who have embraced the power of fear to make others do what you want them to do and one of the big problems with that is that, while fear is a terrific motivator, it is only ever a temporary one. And fear doesn’t allow you to have relationship with others, so if you’re intent on controlling them for long, you either have to continue to ratchet up the fear factor or you have to worry about their retaliation. (Of course, one other solution is to entirely eradicate the “other” so that you don’t have to consider being in relationship at all.)

In hooks’ love ethic, everyone has the right to be free, to live fully and to live well. Everyone expresses themselves honestly and openly and with a view toward living their ethic in everything they do and, in doing so, they are investing in their own individual growth and the growth and happiness of everyone else. Individuals in these kinds of communities recognize the humanity of the other individuals at every turn even if they don’t agree with them. In acknowledging the humanity of others, there is no desire to “win” or rule over another, there is only a concern for the good of all and the acceptance that nobody can ever have all that they want because that is not good for the community.

The irony in the present situation in the Middle East is that everyone’s actions are rooted in fear, even as they are doing their mightiest to instill terror in the hearts of their opponents. And when we act out of fear, we cannot hope to accomplish anything but inciting more fear and anger. This cycle is endlessly destructive and while we may gain momentary feelings of righteousness as we claim small victories, we

have not made any lasting, sustainable efforts toward peace.

In the case of the violence in the Middle East, Benjamin Netanyahu has been very clear that the goal of attacking Gaza is to shut down the tunnels that Hamas has built from Gaza into Israel’s territory. They are afraid and, goodness’ knows I don’t fault them for that. Their fears are justified, given the violence Hamas has rained down upon Israel thanks to the tunnels. But in disproportionately attacking the civilians in Gaza, what Israel is doing is showing that they can instill fear in Hamas, that they can be scarier than their enemy in hopes of what – convincing them that Israel is mightier and they ought to just give up? Even if Hamas did concede that point for now, if they ever hope to get any power again, they will have to invent some way to be even more frightening in the future. And the Palestinians are not likely to ever forget the horrific numbers of innocent civilians who fell prey to Netanyahu’s military which means that the prospects for a peaceful solution are even farther away than they were before.

There will always be someone who will come along and threaten to take what you have – your feeling of security, your home and possessions, your family. And we can set up fences, locks, alarm systems, but as long as we are operating from a place of fear, we are focused on what we might lose instead of what we already have, what is most important. If we can learn to retreat to a place of “enough” instead of continually visiting the well of “I need/deserve more,” we won’t feel threatened by others and worried that they will take what is or might one day be “ours.” And if we can build communities based on everyone taking the courageous, incredibly difficult step of extending a hand and trusting in each others’ humanity, we might just begin to find solutions that are rooted in love one day.