evidence of how we are failing our children. The fact that we have systems in

place to mobilize grief counselors within our communities, that there are

protocols and sample dialogues to help parents talk to their children about gun

violence in their schools tells us we are doing something wrong. That a “popular,” “happy” high school

student from a “prominent” family could post his anguished feelings multiple

times over a period of weeks on Twitter prior to shooting his friends and

turning his weapon on himself and the media headlines read “Motive Still

Unknown” is shocking to me.

am not blaming the family and friends of school shooters for not intervening,

not anticipating that they will react this way to their deep sadness. I am

saying that we as a society are failing our kids in an elemental way by waiting

until something horrific happens to talk publicly about difficult emotions

instead of teaching our kids how to recognize and process those emotions throughout

their lives.

vital things we know are at play here. First, adolescent brains are literally

wired differently than adult brains. The brain of a teenager is subject to

emotional storms that are not yet mitigated by logic, primarily because that

portion of their brain is not yet fully developed. When a teenager is feeling

strong emotions, they are not being ‘dramatic’ or ‘over-reacting,’ they are

simply responding to the chemical reactions swirling around in their heads. To

expect them to push aside or disregard those biochemical impulses is simply

unrealistic. Instead, we have to teach them to mitigate those responses, to

acknowledge their feelings and process them appropriately, but all to often we

expect them to “get over it” or we feel uncomfortable when they are upset and

we minimize their feelings to make ourselves feel better.

spend billions of dollars each year teaching our children to read and write, to

apply mathematical formulas to complicated problems, to find patterns in

history and science, and we neglect to talk to them about what it means to be

human. While it is vitally important to have these kinds of conversations within

family systems, it is equally as important to acknowledge these emotional

challenges within a wider audience, to normalize them as much as we can. If we continue to send the message that

learning to identify and process deeply painful feelings is a private endeavor,

we are missing the opportunity to show our children that they are supported

within a wider community, that they are not alone.

second thing that we know is that violence is often rooted in disconnection.

People harm others when they feel powerless, often because they are struggling

with ideas of their own worth or their place within the community. When an

individual does not feel part of the system or supported by it, they are more

likely to objectify and dehumanize the other people around them. It is through

that objectification that the threshold for violent acts is lowered – it is

much easier to harm someone you don’t feel connected to, that you have

demonized. Our educational system emphasizes individual accomplishments and

competition, values independence, and isolates students who are ‘different,’

both academically and socially. Without some sort of social-emotional education

that acknowledges the developmental stages of teens and tweens within the

context of the demands placed on them, we cannot expect them to flourish. We

may be raising a generation of students who can compete in the global economy,

but without teaching them what it is to be human, to experience pain and

rejection, to accept discomfort and work through it, we are treading a

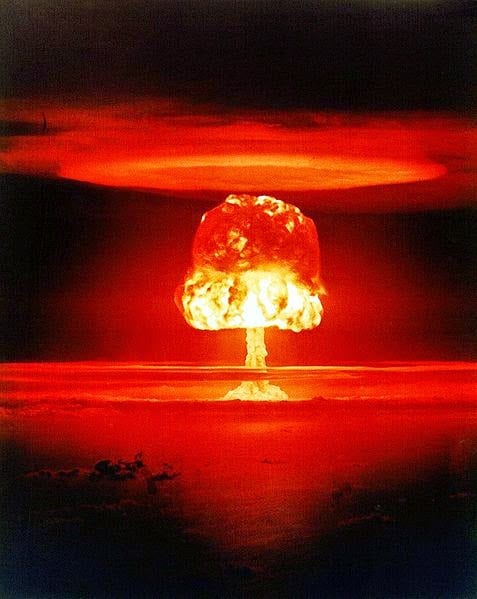

dangerous path. Every time our children cry out in pain we are presented with

an opportunity to listen, to validate those feelings, to model empathy and compassion

and to teach them how to navigate those difficult times. This isn’t about

individual or family therapy, this isn’t about mental health treatment, this is

about acknowledging that our children are whole human beings who are developing

physically, mentally and emotionally and ignoring their social-emotional

development is creating a problem for all of us. Our children are killing each other to get our attention.

What is it going to take for us to start listening to them?