You know that phenomenon when you notice a pattern somewhere and you can’t believe you hadn’t seen it before, and suddenly you start seeing it everywhere? It’s even more eye-opening when there was something you thought was a little ‘off,’ but you couldn’t quite figure it out and then, once you do, you realize it’s a cancer. Hindsight and all that.

I volunteered to be part of a task force for my local school district in 2018. Our job was to dig deeply in to the “highly capable” program and come up with ways to make it less elite (less white, less geared toward rich families, less racist). We spent months looking at data, examining the history of the program, the laws surrounding it, the myriad ways the district had tried to identify and serve kids with extraordinary academic prowess over the years, and how other districts were doing it. It was no secret that our system was deeply flawed from beginning to end.

We weren’t the first group of folks to ever attempt this here. Indeed, there had been a similar task force just a few years earlier that had done the same thing – volunteering hundreds of hours of their time to come up with recommendations they put forth to the district, many of which got a head nod and a sad, “we wish that were possible” before retiring to the packet of information to be passed along to the next task force – us.

We were a fairly diverse group of parents, educators, and community members – cutting across racial and ethnic lines, but not really across socioeconomic ones. I mean, if you have to be able to offer your labor for free for 18 months and show up at prescribed times in a central location, it’s not exactly feasible for many folks, is it? But we did our best to try and bring voices in to the room that may not have been represented.

I think it was around month 12 that I finally figured it out. And now I can’t unsee it. And I also can’t not notice it everywhere I look.

We were never going to be able to make radical, substantive change to this system because no matter what we did, the system had a way of continuing to center itself.

Supposedly, the public school system was created to benefit kids and society (well, mostly society if we’re being honest). Over time, we started thinking that the benefit to kids would work itself out if we just threw a little money and a bunch of rules at it. We kept adding layers and layers of bureaucracy (standardized testing, mandatory minimum days/hours of instruction, core class requirements, etc. etc.) without ever looking at the impact it truly had on society or the kids. And even if we recognized that some of those things were detrimental or not really serving the kids, the system had invested so much time and money in to setting up the scaffolding for those things, we weren’t about to abandon them. When we went in to that task force work, it was with the goal of increasing equity, but that has to do with the kids, what’s good for them, and the system kept saying, “how can we do that?” or “how can we pay for that?”

It’s the same with our “health care” system. We don’t center the patient – we center the system. Asking how we can afford it, or wringing our hands as we think about the logistics of dismantling the private insurance system and the administrative bureaucracy fed by it is centering the system. The system has taken over and become our driving, bedrock force in every decision. We consider the needs of the individuals only within the context of the system’s needs being met, not the other way around. We bend over backwards to try and find solutions (add layers of bureaucracy) to protect the system. That’s why Joe Biden wants to have a private insurance option and just expand Obamacare. Not for the good of the collective, the good of the individual human beings, but so we don’t disrupt the system.

That is why women and people of color and folks with disabilities and those along the gender and sexuality spectrum are the progressives – because they have historically not ever been served well by the systems we put in to place and they are willing to center the collective, the human beings. But the white men who are served really well by capitalism, indeed, who have their identities tied up so deeply with capitalism and colonialism, feel threatened.

So many of the things we take for granted – 40-hour work week, retiring at 65, the stock market as the measure of the economy – those are things that were set up to benefit the system. If we don’t question them, when we want to make things better for the people who aren’t served well by the system, we just add little appendages here and there. Overtime pay, retirement jobs at Walmart as greeters, no-fee online investing opportunities. WE ARE CENTERING THE SYSTEM.

But here’s the thing: this time in history right now is showing us that we can live outside the system, that we can find ways to center people.

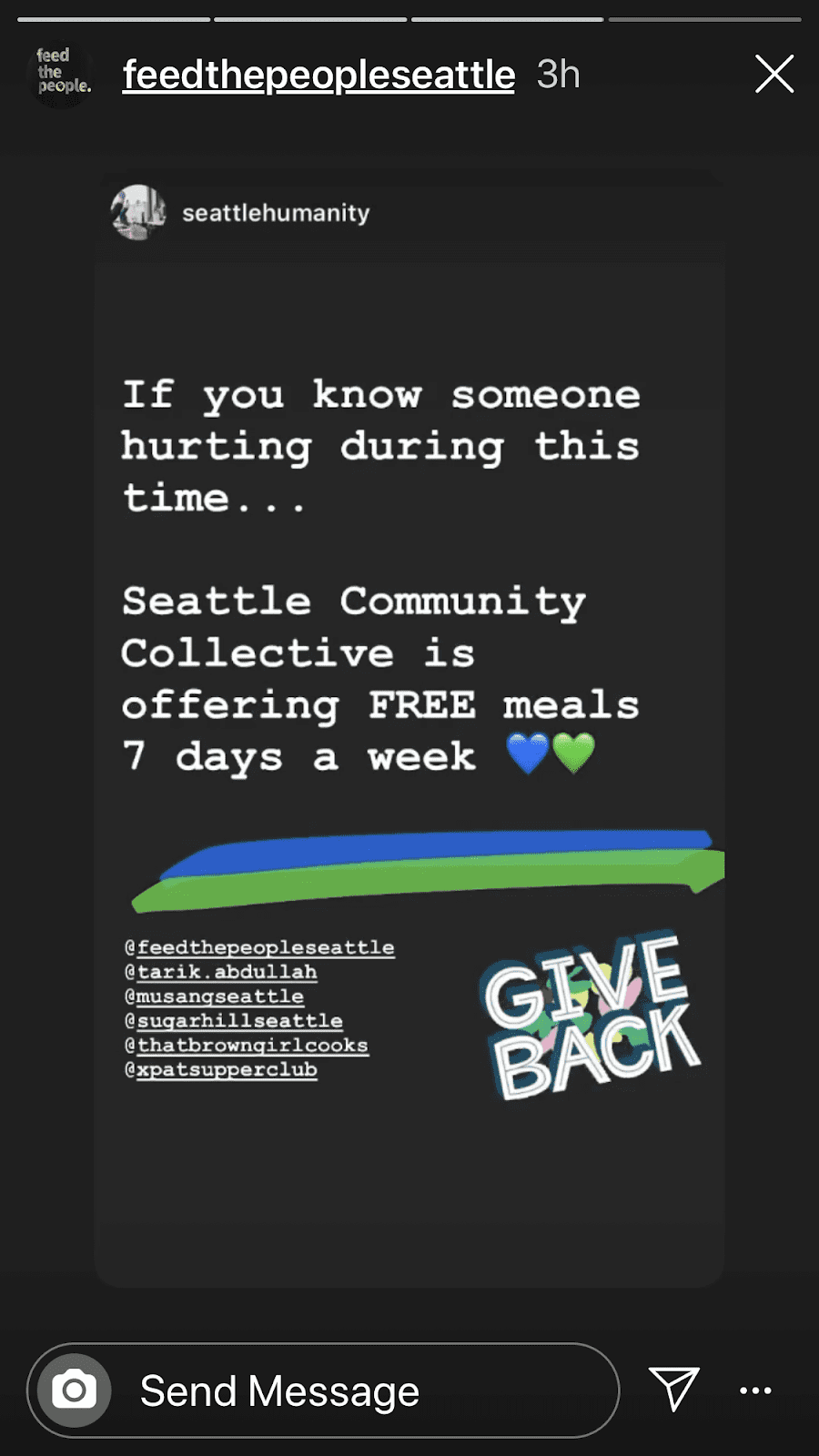

Do you know how vulnerable people are getting fed right now? Not through systems – in SPITE of systems. There are collectives springing up all over the place to feed people who need it, neighbors offering to shop for other neighbors and deliver groceries to their doors, donations of gift cards to folks in need, people sending money through Venmo to people they’ve never met before. People centering people.

Do you know how people are going to survive not paying their rent? Not because of systems. The systems aren’t responding quickly enough – there are too many layers to cut through. If we suspend rent payments, we have to suspend mortgages for the landlords and if we do that, we have to bail out the banks who hold those mortgages and then people will be mad that we bailed out the banks, etc. etc. But local folks are banding together to form coalitions that are demanding that renters not be evicted and that rent be suspended – without penalty or interest – for now. There are millions of dollars in grant money flowing to artists and small businesses impacted by this because of individual people who centered the collective good.

Small farmers who were de-centered in favor of the system are banding together to find ways to get food to folks who want it. And in many cases, it’s working. Because we are centering people, not systems.

The huge hospitals that are cutting pay for healthcare workers because their clinics have all but shut down for elective visits? They’re centering the system. They are saying “we can’t pay for this” instead of saying “we will do what it takes to make sure that everyone is taken care of.”

The politicians who refuse to order shelter-in-place rules? They’re centering the system. They are saying “having people out buying and selling things in my community is more important than the health and well-being of the community.”

That pathetic stimulus package check you may or may not get? Centering the system. Even it doesn’t address everyone – college students who live on their own but are still claimed as dependents on their parents’ taxes get no check, social security beneficiaries whose threshold income is too low to file a tax return get no check.

The thing is, the system will tell you that it is working for the greater good, for the collective. But it isn’t. The system is working for itself. Anytime you hear “what will that cost?” or “we can’t logistically manage that,” you are witnessing a system centering itself. These systems are crumbling for a reason right now and that is because they rely on people to make them work, whether they serve the people or not. The system will try to coerce a certain number of people to stick with them by any means possible (overtime pay, threats of job loss, appealing to the needs of others), but make no mistake, your needs are not paramount.

One evening toward the end of our task force work, I walked out in to the dark parking lot alongside a teacher who works with students with special needs. We talked about our frustration and our hope that we hadn’t just been wasting hundreds of hours of our own time to come up with strong, bodacious recommendations that would simply be cast aside by the Superintendent. I talked to her about my theory of systems centering themselves and she got teary and it was then that I realized she was the inflection point and I felt overwhelmed for her. In a system that centers itself, if you are a teacher or a health care worker who truly centers the person you’re supposed to be serving, you are caught in a vise. In order to keep your job and do the work you do that you believe is so vital, you have to bow to the system. But in order to serve the children or the patients who come to you in the way they deserve to be served, you have to eschew all of the principles the system wants you to embrace – you have to be creative, find workarounds, often use your own resources to go above and beyond. The system is hurting us all if we truly want to center people and the collective good, not only the individuals being served, but those who are exhausting themselves and their resources to be the conduit between the systems and the collective.

It’s time for another way. May we use the next several weeks to dismantle the systems that center themselves. May we find the strength and courage to answer the question “how can we pay for that?” by saying “it doesn’t matter – we have to do what is right.” May we remember that if we value each other, we can look to the underground groups that are springing up to help each other outside the system and learn from them. This truly is the Matrix and we’re seeing the glitches.

|

| Image Description: a spiral tattoo with the words “You are here” pointing to a specific spot on the spiral |

I don’t know about anyone else, but in my life, when the Universe decides I need to make a big leap to the next phase of my personal evolution, it tends to pile on. As in, give me many instances of the same kind of bullshit over and over again until I start to pay attention and recognize it for what it is.

Thus, the last two weeks or so have been a lot. To say the least. A whole lot.

I won’t go in to the details, but I finally figured out this morning that this particular lesson is about making choices, pretty consequential choices. And that’s something I can have a hard time with because I am not one of those “trust your gut” kind of people. My gut is either not particularly loud, or I have an overdeveloped connection between my gut and my brain such that my brain is always always always weighing in, considering options, looking at potential outcomes and thinking of unintended consequences.

When this happens, I spin. The part of my brain that makes decisions goes very quiet and offline, and the part of my brain that convinces me that this particular decision is incredibly monumental and I’d better not fuck it up rules the day.

So, yeah.

At least three times in the last two weeks, I’ve faced decisions that I considered, second-guessed, made lists about, considered again, tried to divorce myself from, and then ultimately made. And guess what? The world didn’t stop turning.

I know I’m not the only one who worries about making the “Right” choice, but I think I’m learning that what I need to pay attention to more is the right reasons. Meaning, it’s more important to get really clear on my own values and needs and use those as the basis for examining why I’m conflicted. Figure out who or what is being centered in my deliberations.

In this time of crisis, I am reminded that we are all entrusted with caring for each other. that there is nothing more profound or elemental than that.

Today, my youngest daughter got up and went to work, nannying two precious boys she has taken care of for a year – 18-month old twins whose faces spread into grins when they see her, whose arms reach for her, who giggle when she makes silly noises. Who trust her.

I am holed up in my bathroom with a tortoise, having just filled a tub with warm water for him to bathe in, put together a pile of fresh greens for him to munch on, and cranked up the heat so he can roam and explore comfortably.

My pups are fed and walked. I’ve checked in with my oldest daughter who is far away and having to scramble to pack up and move out of her dorm. She and her friends are collaborating, pooling resources, opening up couches and offering rides to each other to ease the stress.

I just got off the phone with my mother’s caretaker, having learned that she is being placed on hospice care as of today, and the facility isn’t open to visitors. “She is so pleasant and lovely,” he says, detailing to me how they are caring for her at this time and encouraging me to call and get updates as often as I want to.

Someone posted in my neighborhood Buy Nothing group an offer to shop for anyone who is afraid to leave home. “How can I help you?” she asked.

Funds are being created for small businesses who are hit hard by the lack of mobility in Seattle.

We are entrusted to each other’s care.

Our strength is in our compassion, not our fear. Care comes in so many forms: a text message or DM, a Twitter post asking if others are ok, feeding our pets or tending the garden, offering thanks and gratitude to those who are working hard to make policy and heal the sick.

We’ve got each other.

We’ve got this.

It’s all we’ve got, and it is a lot.

Let’s take care of each other.

Yesterday, I went to a book launch that was very different from any other launch I’ve been to – for a book I’ve already read that brought me to tears more than once, as a writer, as a mother, as someone who loves people who struggle with addiction. The book is A House on Stilts, written by Paula Becker, and she took great care to bring this book out in to the world in partnership with representatives from agencies in Seattle who help young adults with addiction and homelessness.

More than once, I found myself swooning during the launch. First, when Paula spoke about addiction as a community issue, rather than a personal or familial one. Then again, when Christopher Hanson, the Director of Engagement Services for YouthCare in Seattle used the phrase “unconditional positive regard,” and when all of the panelists spoke about the necessary collaboration between families and social service agencies as we work to craft supports for young people in crisis.

Paula wrote this book knowing that there will be readers who will seek to distance themselves from her story because it is so painful, and many of them will do that by examining her choices and using them to excoriate her and her husband. The book itself is brilliant in the way it combines her personal journey as the mother of someone who fought opioid addiction with the facts about how our communities treat those who struggle and their families. While it is often incredibly sad, it is not a ‘woe is me’ tale or a defense of her individual choices, but a call to action that we must heed if we are to do right by this generation of young people who have been caught in the grip of addiction and all that it bleeds in to – unemployment, homelessness, mental illness, and physical health challenges.

Unfortunately, so many of our public health systems fail to adequately address the needs of young people and families who seek help – especially black and brown people. And over time, the continued failures make it hard to believe that the systems won’t do more harm than good. Threatening to put folks in jail, cut off services, remove children from their parents’ home – these are not ways to heal, and they are certainly not ways to engender trust. If you are a person who has been denied services or threatened with punishment of some sort over and over again, the likelihood that you will continue to ask for help gets smaller and smaller, and you become more isolated and more at risk of harm.

When families are expected to support a loved one with addiction in isolation, they quickly become overwhelmed. I have had personal experience loving and supporting someone who is constantly in crisis – waiting for the phone call that will tell me they are injured or dead, getting the phone call with an urgent plea for shelter or money, holding that person time and again while they shake and sob and say they are ready to get help. The toll it takes on your physical body is real, and the emotional triggers last for – well, decades at this point, and I don’t know if they’ll ever go away. The adrenaline rush that floods your body when you get that call, the shaking, the lump in your throat, the voice in your head that says, “it’s happening again and I have to marshall the strength to manage it,” are nearly impossible to ignore. If we do not have others to reach out to for help who don’t have the same visceral ties to the person struggling (and, thus, can help in different ways that are often more effective), we are quickly depleted in every way.

When partnerships are rooted in genuine care and a purposeful dovetailing of skill sets and resources, they are amazingly effective. As a family member or individual who is struggling, finding those people to partner with is challenging at best, and finding partners with adequate funding and training and physical space is even harder. When we can find them, as mothers and fathers and caregivers, we are allowed to set boundaries that enable us to continue to function and take care of ourselves. Paula’s story is not unique, and it is imperative that we listen to it keenly. Her willingness to share the pain of her journey with her son’s addiction and her ability to hold it up as a call to action for all of us to come together and recognize this as a community crisis is courageous and wise. Find this book, read it, and reach out. Our elected officials need to know that we want them to support funding for the agencies who are tasked with helping individuals with addiction. They need to know that we believe this is a crisis for all of us, that we all belong to each other, and that nobody can do this alone. Even families with financial resources cannot buy their way in to rehab facilities if there are no beds available.

Perhaps the most striking thing Paula said during the book launch was this: “…you cannot starve someone in to recovery, nor can you shame them in to it. I ask you to have compassion – the next time you see someone who is homeless, don’t look away. Offer a smile, meet their eyes, ask if they are hungry and buy them a sandwich.”

The beauty of this book is that compassion not only means kindness toward that one person you see struggling, but it also means that we need to work to build systems of compassion that support our community members in their endeavors to heal. We do, truly, all belong to each other. May we start acting like it, soon.

We know the power of story to motivate and connect people, to convince and add color. But I am increasingly aware of how storytelling has become co-opted over time, bent and twisted to be used as a power tactic or a marketing tool.

Story is a tool – it used to be a tool to educate; elders would tell fables and parables to illustrate concepts. It is used to entertain, to take us out of ourselves, and it is an incredible way to build empathy. Telling our stories helps us release them from our bodies and, in the right setting, reminds us that we aren’t alone.

In the last several decades, story has also become a way to ask for validation, acceptance, consideration. And while that might not seem like a bad thing on its face, in the context of people without power telling their stories to people in power as a plea for empathy or understanding, it feels heavy in my gut. It feels more and more like justifying our existence, defending our choices, hoping to be considered equally human and deserving of care.

Many years ago, I began interviewing women about their stories. Specifically, their stories around being pregnant and having to choose whether or not to stay pregnant. I was increasingly frustrated that the political tug-of-war around abortion rights seemed never ending and I was certain that the conversation was all wrong. My hope was that centering the stories I wrote on the issue of choice would shift the spotlight a bit and add depth – open people’s eyes to the notion that the issue wasn’t two sides of the same coin, but far more complicated than that.

I had fully bought in to this new notion of what story was for. I was using these stories to not only educate people, but to convince them that these women deserved their consideration.

Sharing our stories is an enormous act of vulnerability. Opening ourselves up and shining a light on the parts of us that feel different, look different, are different is incredibly courageous, especially if the listener is not simply a vessel, but a judge. And while story is known for building empathy, it shouldn’t be the key that opens the gate to empathy. If, in telling our stories, we are hoping to gain acceptance and validation of our worth, and the listener is the one who gets to grant that (or not), story has become twisted and co-opted.

The notion of needing to tell our stories so that people in power will acknowledge us and tap us on the shoulder with their scepters, allowing us entry in to the world of Worthy Humans is abhorrent to me. We need to start with the belief that we are all worthy and cherished. People with disabilities, people of color, transgender or non-binary people, women, elders, childless folks, immigrants – nobody should have to tell their story in order to be regarded as worthy of respect. Nobody should have to show their scars and bare their souls so that they can be deemed worthy of care and honor.

Our stories are reminders that we are not alone. They teach us about the depth and the breadth of human experience, but they should not be a pre-requisite for civil rights, for love, for worthiness. The power of our stories is that they help us connect to others, and to use them as currency for equality and humane treatment is wrong.

I admit that when I started my interview project, it was with the intent to use the stories as political capital. I hoped that they would be published in a book that would reach the ears of people in power, that the stories would shift something inside them fundamentally and convince them once and for all that reproductive rights are vital, foundational, human rights. The women who spoke with me trusted me and, in some cases, had never told their story to anyone else but me. I was powerfully moved and believed that it would make a difference. These days, I resent the fact that I should have to tell my story in order to gain agency over my own body, in order to maintain or regain my civil rights and be seen worthy of that by people in power.

I believe in the power of story. When someone trusts me with their truest, deepest truth, it is a gift I do not take lightly. As receivers of story, we have an opportunity to be deliberate and generous with our listening, to recognize that we are being given a gift. I have felt the significant difference between telling my story to someone who is willing to hear it, contain it, hold it and reflect back to me that I am not alone in my difference, in my pain, in my perspective and telling my story to someone in an effort to get them to recognize my humanity. The first instance feels healing and fuels connection – the second feels defensive and frantic and defiant. Sharing something profound in an effort to find community is expansive. Sharing something profound as a way to justify my existence or worth or right to have agency over my body is like always being a step behind, and it reinforces the power differential between me and the receiver.

I appreciate the people who gather the courage to speak for themselves and others – the ones who testify in public hearings in support of accommodations or policy shifts or funding sources. I simultaneously lament that movements like #shoutyourabortion or #youknowme have to exist, that we have been forced to use our stories as justification for our choices, to plead for help from those in power. It isn’t as though there is some tipping point, some critical number of stories that are told that will shift the narrative in favor of acceptance and compassion, in favor of the foundational belief that we are all human and, as such, equally deserving of the right to live freely, move through the world without obstacles in our way or a target on our back.

Until we can start at a baseline of humanity for all, equal rights, and acknowledgment of the historical systemic ways we oppress women and people of color and folks with disabilities and non-binary gender expression, etc. etc. we will not be able to truly hear the stories of our fellow humans. We will always be looking for the “hook,” the seminal difference, the spark that makes us say, “Oh, ok, you’re not like those other __________.” But in my heart, that’s not what story is about. Story is about bringing us together, reminding us of our connections, and reinforcing the power of being acknowledged.

Part One is here.

This one’s for Birdie.

Oh, Birdie. I don’t know you, but I know you. We’ve never met, but I hear you.

Birdie left a comment on the previous post that I’ll excerpt. She wrote, in reference to seeking professional help to process the trauma she experienced as a child, “…I can’t be helped and soul destroying because it means I am really messed up. I am so afraid of opening Pandora’s box and becoming unable to deal with what lies waiting. But I am tired. Tired of never being happy. Tired of always feeling anxious. Tired of always, always being afraid.”

Talk about ‘bringing the whole house down.’ That’s what compartmentalizing does to us. It makes us feel safe for the moment, but it ultimately destroys us from the inside out. Because when we hide those things away – either for later or for what we think is forever – we deprive ourselves of community and support.

Human beings are social creatures. We are designed to live with each other. Our bodies respond on a molecular level to touch and interaction from each other – our adrenal glands activate, our neurological systems light up, we secrete hormones that make us feel safe and loved and happy when we let ourselves share experiences with other people (and animals – never underestimate the power of a soft, furry creature to snuggle up to).

But when we wall of parts of our human experience, we relegate ourselves to holding what are often the most traumatic and painful things all by ourselves. It is akin to telling everyone that we would like their help carrying the 20lb. box of papers but that they can go home after that because we’ll figure out how to lug that 200lb. desk in the corner alone. Or not at all. There are so many reasons we do that – shame, denial, overwhelm. We hate that desk. Maybe we will just leave it there and never look at the corner where it sits, heavy and ugly.

It is counterintuitive to expect ourselves to bear the heaviest weights alone. We can’t do it, no matter how much we want to or how hard we try. And we aren’t designed for it. But when we compartmentalize, that’s what we’re setting ourselves up for – isolation, solo work.

So, Birdie, if you’re reading this, know that even as you wait for a therapist who is the right one to help you work through that pile of stuff you’ve hidden in the corner, you aren’t alone. While it’s important to find skilled counselors to help us dig through the deepest traumas, in the meantime, there are people out there who will help you support the weight of what you’ve got sitting there. Let them. Don’t worry about whether they’ll get something on their clothes. Don’t think about how it smells or what it looks like. Just know that, together, we can bear so much more weight than we think we can, and that there are people out there who care for you who would like nothing more than to hoist up a corner and take some of the pressure off of you. That’s how we’re designed. That’s what we do for each other. And while it takes some practice (often, years of practice), that feeling of relief that you get when others come along to help bear the load is the beginning of healing.

Thank you for your courage.

You will get there from here. I know it. You won’t do it alone, but that’s the sweetest part of this. You’ll discover, along the way, which of your friends and family is really great at unpacking, cleaning up, and showing up. Let them. Don’t apologize. It’s how we’re designed. Embrace it and know that you were never supposed to hold all of this by yourself.

I am reading my first book by bell hooks. I have read quotes of hers before and come across people who think she is absolutely brilliant and yet, I have never once picked up a book by her. Until now. And to be honest, I don’t even really remember what made me pick up “All About Love: New Visions,” but it is quickly becoming a tome to set next to the likes of David Whyte’s “The Three Marriages” and anything by Brene Brown to read over and over again. I have taken so many pages of notes I’m running out of space in my notebook and I am only about 70% of the way through it.

hooks’ meditations on every kind of love from friendships to family to intimate, romantic relationships to self-love are so simple and profound that I am stunned again and again. And, as I often do, I find myself stopping mid-page to muse about the ways in which her philosophy pertains to different aspects of my life and pop culture. The fact that her thoughts feel so incredibly universal to me is one reason why I suspect I will be able to read this book many times and find some new perspective during each and every reading.

She begins by defining love in a way I’ve never heard it spoken about before and, yet, it feels absolutely right to me. She uses M. Scott Peck’s definition, the will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth, as a springboard, and adds, “To truly love we must learn to mix various ingredients – care, affection, recognition, respect, commitment, and trust, as well as honest and open communication.”

She has chapters on every imaginable application of love but in light of what is happening in the Middle East right now, I am particularly struck by her chapters on community and what she calls a “love ethic.”

I have been called hopelessly idealistic and a dreamer most of my life. I own it. And so, in that spirit, I began thinking about what the world would look like if we embraced the notion of a love ethic, cultures rooted in mutual respect and acknowledgment instead of materialism and consumerism and money and power. In this kind of society, it would be absolutely necessary to address our fears and take daily leaps of faith. In this kind of society, we would be required to forego the possibility of having everything we want in order for everyone to have some of what they want. In our current model, we are encouraged to think constantly about what we as individuals want which sets up this endless cycle of desiring and attaining and assessing and desiring more. We are always comparing what we have with what we don’t have, what we have with what others have, and we will always come up short. In our current model, where possessions equal success equal power, we are tricked into thinking that more stuff will make us happier and we dehumanize other people who get in the way of us having more stuff.

When I think about the daily violence happening in Gaza and Syria, I see a cycle of fear and entitlement. I see groups of people desperate to have exactly what they think they need and willing to go to any length to get it. I see militaries who have embraced the power of fear to make others do what you want them to do and one of the big problems with that is that, while fear is a terrific motivator, it is only ever a temporary one. And fear doesn’t allow you to have relationship with others, so if you’re intent on controlling them for long, you either have to continue to ratchet up the fear factor or you have to worry about their retaliation. (Of course, one other solution is to entirely eradicate the “other” so that you don’t have to consider being in relationship at all.)

In hooks’ love ethic, everyone has the right to be free, to live fully and to live well. Everyone expresses themselves honestly and openly and with a view toward living their ethic in everything they do and, in doing so, they are investing in their own individual growth and the growth and happiness of everyone else. Individuals in these kinds of communities recognize the humanity of the other individuals at every turn even if they don’t agree with them. In acknowledging the humanity of others, there is no desire to “win” or rule over another, there is only a concern for the good of all and the acceptance that nobody can ever have all that they want because that is not good for the community.

The irony in the present situation in the Middle East is that everyone’s actions are rooted in fear, even as they are doing their mightiest to instill terror in the hearts of their opponents. And when we act out of fear, we cannot hope to accomplish anything but inciting more fear and anger. This cycle is endlessly destructive and while we may gain momentary feelings of righteousness as we claim small victories, we

have not made any lasting, sustainable efforts toward peace.

In the case of the violence in the Middle East, Benjamin Netanyahu has been very clear that the goal of attacking Gaza is to shut down the tunnels that Hamas has built from Gaza into Israel’s territory. They are afraid and, goodness’ knows I don’t fault them for that. Their fears are justified, given the violence Hamas has rained down upon Israel thanks to the tunnels. But in disproportionately attacking the civilians in Gaza, what Israel is doing is showing that they can instill fear in Hamas, that they can be scarier than their enemy in hopes of what – convincing them that Israel is mightier and they ought to just give up? Even if Hamas did concede that point for now, if they ever hope to get any power again, they will have to invent some way to be even more frightening in the future. And the Palestinians are not likely to ever forget the horrific numbers of innocent civilians who fell prey to Netanyahu’s military which means that the prospects for a peaceful solution are even farther away than they were before.

There will always be someone who will come along and threaten to take what you have – your feeling of security, your home and possessions, your family. And we can set up fences, locks, alarm systems, but as long as we are operating from a place of fear, we are focused on what we might lose instead of what we already have, what is most important. If we can learn to retreat to a place of “enough” instead of continually visiting the well of “I need/deserve more,” we won’t feel threatened by others and worried that they will take what is or might one day be “ours.” And if we can build communities based on everyone taking the courageous, incredibly difficult step of extending a hand and trusting in each others’ humanity, we might just begin to find solutions that are rooted in love one day.

According to some, I “rescued” my 14-year old today and I shouldn’t have. Ironically, one of the first things I saw on my Facebook feed this morning was an essay in Brain, Child that spoke to this exact issue and would probably have placed me squarely in the camp of “helicopter parent.”

I beg to differ.

As a child, I was fully indoctrinated into the world of toughlove. The world of “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” and “learn to succeed on your own.” And, largely, I benefited from those lessons – the teachers who let me puzzle through challenging lessons without giving me answers, my dad refusing to bail me out when I got myself into debt because I didn’t think ahead, other adults in my life who showed me they believed in my abilities by not stepping in to forewarn me of some misstep I was about to take. But there were times when I would have done much better knowing that I had support, times when I believed that independence was tantamount to connection and that being able to take care of myself was more important than asking for help. It would have served me very well to know how to even gauge my own thresholds, to know how to assess when I was out of my depth and needed a lifeline. Instead, the message I internalized was that I needed to be fully self-sufficient.

One morning a few months ago, I stepped in to the quiet halls of the school my daughters attend. The students were all in classrooms, the sunlight streaming through the windows and bouncing off the shiny locker doors. The receptionist sat at his computer typing away with the dean of staff hovering behind his shoulder. They both looked up in surprise as I tugged on the front door, needing to be buzzed in.

“Lola left this on the printer this morning,” I waved a sheet of paper in the air in explanation. The dean rolled her eyes and shook her head at me. She would have preferred that I let Lola twist in the wind, that she learn a difficult lesson about remembering her own homework. I felt a wave of shame and defensiveness begin to rise up in my belly but I blocked the words before they sputtered out of my mouth. I turned to the receptionist, kindly asked him to hand the paper to Lola at the next break between classes, thanked them both, and left.

Since that day, I have shown up at the school maybe once or twice to drop off basketball shoes or a hastily-prepared lunch for one of my girls. I will defend those decisions unequivocally and here is why.

As an adult, I cannot claim that I never forget anything at home that I ought to have had with me, despite the toughlove lessons I received as a child. As an adult, I have the ability to return home in my car to get the things I forgot or use my debit card to purchase my lunch on the fly. My children do not have that option available to them. On more than one occasion, Bubba has called me from a business trip to plead that I stop by the dry cleaners to pick up his suit because he totally forgot to do it before he left and he will need it as soon as he returns home. Should I refuse him this kindness in an effort to “teach him a lesson?” I think not. And I won’t do that to my children, either. I refuse to let Lola go hungry at lunch in order to impart some false sense of wisdom. Instead, I will offer them the same courtesy I hope my loved ones would extend to me in my time of need.

There are obvious exceptions, and if there is a pattern of behavior that I think needs to be dealt with, I will of course address that in a different way, but it makes me crazy to envision a world in which my daughters are taught that they are the only ones responsible for every detail of their lives. If that were true, we would all live in a house where we only did our own dishes and nobody else’s and we wouldn’t be able to count on each other to remind us of important events when our brains (and calendars) are overloaded.

Some of the examples of enabling the author called out in her essay felt to me as though they were oversimplified in the making of her point. There is a difference between ‘rescuing’ our children and teaching them life lessons that will serve them well one day. I long ago stopped doing all of my girls’ laundry for them, but if Eve has hours of homework to do and her basketball uniform needs a 12-hour turnaround, I’ll offer to help out if I have time. I don’t pay the girls’ library fines if their books are overdue, but when I realized that it was getting to be a problem, I offered to help them brainstorm ways to make it easier to find and return books they had checked out. Instead of letting them believe that there are only two solutions (Mom does it or I do it), I hope I can teach them that we are all in this together and that makes it a better world for everyone. Yes, they are ultimately responsible for their own stuff and their choices and behaviors, but there are times where you just mess up and other times when you can’t solve the problem all alone. I know that the only thing stopping Eve from zipping home to get her own running shoes and socks today at lunchtime was the fact that she isn’t old enough to drive. Given that we live five minutes from school, I have absolutely no problem heading down there to drop them off because I think the lesson here is that I’m willing to help her out when I can. I would rather raise my kids to be compassionate team-players than super-responsible, hyper-independent individuals who refuse to help someone find their misplaced keys because “it isn’t my problem.” I would rather raise them to know that it’s okay to be human and ask other people for help occasionally, that getting assistance doesn’t lead to dependence and lethargy and laziness. Most of my early adult life was spent pushing people away, feigning that I was capable of handling anything that presented itself. While I felt a great deal of pride in my accomplishments, I was also scared of the next thing that might come along that I might NOT be able to deal with and I was pretty damn lonely. It feels a lot better to know that someone has my back and if my kids learn that I’m there for them when they can’t do for themselves, I will be able to sleep soundly at night, whether or not you label me a “helicopter mom.”

|

| Photo from Seahawks.com, Rod Mar |

The Pacific Northwest is my home and there are dozens of reasons I love living here. But thanks to last night’s Superbowl victory by the Seattle Seahawks, it just got a little more exciting.

I grew up with sports – football chief among them. The Miami Dolphins won the Superbowl the same year I was born (and, unfortunately, haven’t won another one since) and even though I grew up on the West Coast, I spent my youth cheering for Bob Griese and team. My dad patiently taught me about holding calls and 2-point conversions and there were always two or three Nerf footballs lying around our yard. There were other sports we loved, to be sure, but following football was as much part of our lives as going to church on Sunday, and it was something we did as a family.

In high school I dated the quarterback for a while and froze my butt off in the stands every Friday night cheering on our team. I loved the rush of sitting with my friends, doing the wave, and rising as one entity, screaming with joy when one of our boys hit the end zone.

I watched helplessly in college as one of my friends was hit so hard he ended up paralyzed and suffered bleeding in his brain. He never recovered and spent the next few years of his life in a nursing home where he ultimately died of the brain injury. The community of students and staff rallied closely around his family and Eric’s room was rarely empty for the remainder of his days.

For the past few weeks our town has been a frenzy of excitement and I have been reminded of the power of community. A few years ago, the team and its supporters began using the phrase “12th man.” The idea picked up steam and while it may not have originally been intended, the fans of this team have become an integral part of its success. 12 man flags fly all over town and at the end of every victory, both the coach and players thank the fans. Beyond giving the team a home field advantage by generating so much noise the opposing team can’t hear each other, the fans have folded the coach and players into the life of the town so deeply that they have become intertwined. The players appear in local hospitals and schools, and the owner has a rich history in Seattle as well.

There is something really amazing about feeling as though you are truly a part of your team. However absurd it sounds, the sentiment of ownership, of pride, is palpable in this town right now. From the young coach who folks thought couldn’t lead an NFL team to victory to the quarterback who was told to stick to baseball to the owner whose major accomplishment prior to buying the Seahawks was helping Bill Gates start one of the most successful technology companies in the world, this team was built on hard work and a dream. (Okay, yes, and a boatload of money, but not the most money in the league by any stretch of the imagination.) I love the fact that prior to this Superbowl, none of the players on this team had a championship ring. Each and every one of these players got their first Superbowl ring last night. Each and every one of them appears to have taken Coach Carroll’s philosophy of playing to heart: that every minute of every game is as important as another. I would venture to guess that many of the fans are doing the same, given the consistent efforts of their team.

I am aware of the many controversies involved with professional sports and struggle with many of them. Are players being exploited by the league when they are asked to hit and take hits that are increasingly dangerous? Is the game too violent? Is it necessary to pay these players such exorbitant sums of money? Why is the NFL considered a non-profit organization and, thus, exempt from paying taxes while raking in obscene amounts of money? But I won’t deny the feeling of community and camaraderie that comes from cheering for this team who acknowledges the part their fans play in their success. In his post-game speech in the locker room, after calling out each individual player who made a spectacular play, Carroll asked the team to cheer for, “The 12s – there is something that’s so real, they are so much a part of what we do…” I can’t say that I’m not a little bit thrilled that this group of players who had the dubious honor of being the underdog went on to such a resounding victory, and they did it without nastiness or rubbing their win in anyone’s face. As for the fans, so far Seattle has stayed true to its reputation by not letting this win spark riots and looting all over town. I, for one, am happy to see the ‘Hawks go out on such a high note and I suspect their fans will ride this high for a while. There is something powerful about being swept up in the momentum of a group of people all rooting for the same thing, whether its a political rally or a sporting event or a group of friends watching a movie together all pulling for the heroine. It feels good, especially when your team wins.

This week has been, for the most part, a glorious one. The kids happily went back to school after more than two weeks away, leaving me the house and the dog and my writing to focus on which, frankly, is more than enough. The weather has been cold and crisp and the sunrises and sunsets a riot of color that stop me in my tracks as I walk the dog around the neighborhood and listen to his feet crunch on the stiff grass. I am on Day 7 of green smoothies – not something I generally go in for – and am sleeping better and full of energy from the moment my eyes open in the morning. I am due to have work published in two anthologies this month and am working on a chapter for a third that will hopefully come out later this year.

*sketch above from msn news coverage of the Holmes trial

But life is yin and yang. Balance. Give and take. And it is with a heavy heart that I go through my day listening to the radio programs that feature speakers debating gun policy in the United States and highlight the events of the trial that is beginning for James Holmes, the man who shot moviegoers in Aurora, Colorado last year. I have been moved, more than once, to shut the damn thing off simply to avoid shrieking in frustration. I do believe we are going about this all wrong. I honestly do. As the NPR commentator detailed the preliminary hearing in Colorado on Tuesday, he wondered aloud whether Holmes will plead insanity and, if so, how that will impact the victims. He asked whether the defense attorneys were ‘laying the groundwork’ for evidence that Holmes was not in his right mind when he planned and executed his attack on the movie theater.

I was struck dumb.

I am not certain that it matters what name we give to the affliction that Holmes has. I am fairly certain that most everyone would agree that any individual who could injure another human being purposely is not acting in their highest capacity. Imagine that a decision is made that Holmes was not sane at the time of his attack. What then? Presumably he would be sent to a facility that would treat him for his mental illness in lieu of or until he can serve a jail sentence. Many people would say that he is being let off the hook if this happens. That he is not paying properly for his crimes. There are those out there whose notion of justice includes Holmes dying at the hands of the state.

Because what happened to those innocent moviegoers should not happen to anyone.

It shouldn’t.

But does that mean it should happen to the perpetrator? I know he may not be ‘innocent’ by definition, but what if some horrific past crime against him comes to light? What if he was tortured by his parents or bullied and tormented by classmates or co-workers? It doesn’t justify his actions, by any means, but how far are we willing to go back to see whether we can find a true innocent? And does perpetuating the cycle of harm really solve anything? Does it really end up in “Justice?”

We have a culture of good vs. evil. We have built this notion that we can root out bad spots like bruises on bananas, cut them away, and leave only the good behind. It is that idea that gave us turberculosis sanatoriums, leper colonies and prisons. But until we discovered the causes of TB and leprosy, we were destined to fill up those colonies over and over again because we had no understanding of how to prevent either the disease itself or its transmission. It is the same with prison.

Do we truly understand that each of us has the potential to harm others? We have spent decades studying “criminal masterminds” to determine their motives and have succeeded only in rooting out information that sets these individuals apart even more from the rest of society. We look for the reasons why “that couldn’t happen to me/my kid/my community” in an effort to make ourselves feel safer and look no further.

What if we embarked on a comprehensive system of restorative justice? What if instead of a trial that pits one side against the other everyone involved came together as a cohesive group concerned with coming to a deeper understanding of what happened and its impact on the entire community? What would happen if, instead of vilifying and segregating certain individuals, we took the time to explore their place in the community and their effects on it? What if, instead of directing hatred and anger (both of which are perfectly understandable and justifiable emotions) at James Holmes, we used compassion and engaged in a sincere effort to help him?

Restorative justice moves us away from the notion of revenge or punishment and towards true healing.

But it requires something of us, too. It requires an admission that the entire community is affected when one person harms other members of the community. It requires tacit acceptance that the perpetrator, too, is harmed – often both prior to and during the commission of the act of violence. There has to be a willingness to see the perpetrator as a human being instead of a demon or a ‘bad seed.’ And there has to be a desire for healing, working through complex issues as a group of invested individuals as opposed to a swift sweeping away or walling off.

I know. Pollyanna. And, no, I didn’t lose anyone in the Newtown or Aurora or Virginia Tech mass shootings – or any other mass shooting for that matter. And I sympathize with those who are blinded by rage and pain at the loss of a loved one or the fear that was instilled in them as they prepare to go to the movie theater or lay in a hospital bed recovering from gunshot wounds. I know, beyond the shadow of a doubt, that I would most definitely want to set myself upon James Holmes or the parents of the Newtown shooter and scratch their eyes out, tear their hair, scream in their face until I was spent.

And then, what? Live in a community torn apart and ruled by fear that we may not have locked up all of the bad guys yet? Live in a place that encourages me to protect myself and my stuff at all costs, even if it means taking another human life? Live knowing that this individual may someday come to an understanding of the implications of their actions, but more likely has choked off their own emotions and replaced them with anger or shame? Because here’s the thing: when you cut that brown smear out of your banana, the banana won’t heal. No big deal, given that it’s about to be consumed, but in the real world of human relationships, we need healing. And, unlike a brown spot on a piece of fruit, I don’t believe that it is at all ethical to simply discard a human life like so much trash.

It wasn’t until I saw my molester as a human being that I began to heal my own profound wounds. I spent years in therapy, took lots of different anti-anxiety medications and antidepressants, started yoga, and came to a better place, but the REAL freedom from pain came when I forgave him. Not in person (I don’t honestly even know if he is alive today), but in my heart. That doesn’t mean that I don’t still feel the impact of his behavior in my life and it doesn’t mean I would have the courage to meet him face-to-face if I had the opportunity, although I hope I would. It means that I acknowledge that he made a big mistake and, as a human being, he was entitled to do that. It doesn’t mean that he is absolved of any wrongdoing, especially since I suspect he molested lots of other children as well, but it means that I don’t feel as though I can pass judgment on him and his life. I certainly don’t believe he deserves to be killed for his actions, although I did for many, many years. What I find more compelling is the hope that if any of his victims were ever tempted to perpetuate the cycle of violence he created in their lives, that they are able to stop and be mindful of how it changed them. That they could understand the impact of destructive, angry, behavior on their victims and the community-at-large and ask for help. And I hope that they could find it. That instead of a society that shrinks back from hearing stories of abuse and trauma and stigmatizing or alienating someone who is struggling with the desire to harm others, we can somehow begin to become a society that embraces all of its people and takes responsibility for them in one way or another. That we can come together with a goal of helping everyone be mentally and emotionally healthy and truly acknowlege that their actions have ripples in the community.

Pilot programs that work with restorative justice report significant decreases in the rate of re-offenses. It makes sense. Often, violence is the result of impulsive behaviors coupled with possession of something deadly (getting angry while in a car or happening to have a gun in your pocket when someone pisses you off). If we can educate first-time offenders about what happens to victims of violent crime, make them sit down with the person or family they harmed, with the honest intent of helping them to understand the true implications of their actions, it makes a difference. The other thing that makes a difference is having the honest intent to help the offender. I know that runs counter to much of the emotion that makes us want them to “pay” for their crimes, and when it makes sense, I think that paying monetary restitution is an important piece of the puzzle. To simply lock someone up without offering them education or therapy or truly trying to get to the root of their behavior constitutes placing a higher value on one human life over another and that undermines community. It breaks down trust and collaboration.

We have all made mistakes. Some of us have made enormous mistakes that hurt others immeasurably. The notion of restorative justice allows for the fact that we are all human and uses our humanity as a tool to bring true healing to a community. It involves working through incredibly difficult emotions and, often, cultural or communication barriers but it ultimately sends the message that we are committed to acknowledging challenges and differences and working through them instead of denying them and categorizing them in an effort to make ourselves feel a false sense of superiority and security.

![]()

Thanks for visiting my site. I’m driven by the exploration of human connection and how we can better reconnect to ourselves, our families, and our communities. Aside from my books, I hope you’ll check out my blog, and some of my other writing to find more perspectives and tools.

This site like most every site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

OKLearn MoreWe use cookies to let us know when you visit this website, how you interact with it, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more and for the opportunity to change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on the website and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will impact how our site functions. You have the option to block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. Please be aware that this means every time you visit this site, you will be prompted to accept or refuse cookies.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

Privacy Policy