|

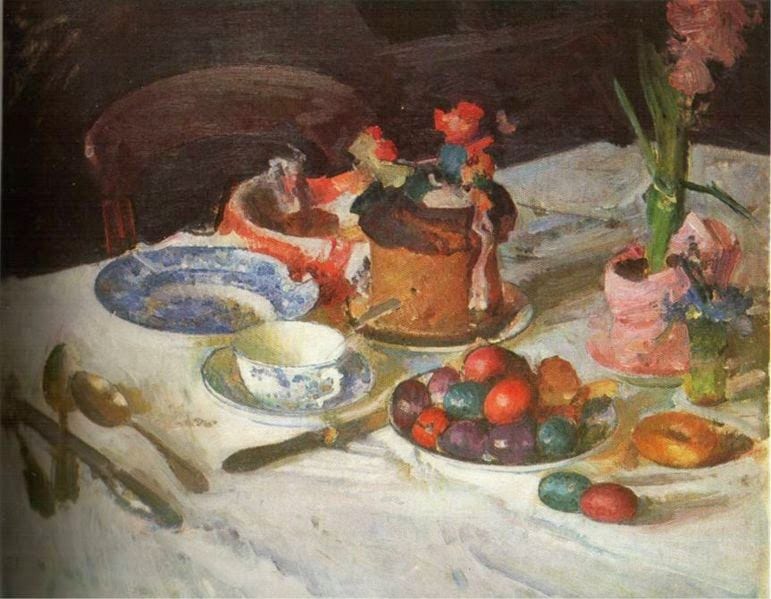

| FhaC protein of Bordatella pertussis |

In December, Eve had whooping cough. We didn’t realize it at the time, but when I finally took her to the doctor three weeks later to see why her cough hadn’t resolved, we figured it out. Of course, by then, she was 90% recovered with just the lingering chest-rattling hack as evidence. Me? I was instantly chastened and laughed to the Physician’s Assistant, “HA! Sign me up for Mother of the Year!” She was quick to let me know that I shouldn’t worry – there wasn’t much they could have done for her anyway. And, hey, now she likely has natural immunity, so it’s all good, right?

The thing is, it didn’t really occur to me that whooping cough was a possibility, mostly because Eve was vaccinated on schedule. I had peripherally heard about whooping cough outbreaks – mainly in high schools around the area – but they never really penetrated my consciousness enough to worry about it. (That said, I will relay the memory of one time a few years ago when a local private high school was closed because of a widespread outbreak of whooping cough and my Facebook feed suddenly reflected a whole lot of vitriol directed at “those people who don’t vaccinate their kids” despite any sort of hard evidence that it was an unvaccinated student who was the cause of the outbreak. That was a little shocking to see, but since I didn’t have a dog in that fight, I left it alone.)

So how the heck did my kid (and all the other high school kids in the area) get whooping cough, especially those who have been vaccinated against it?

There seem to be no simple answers. At least not any based in medicine. I was told (on Facebook) by a friend that my daughter likely “got exposure from another who had not been vaccinated,” but I don’t see how that’s the most likely explanation.

Certainly, it seems that the whooping cough vaccine that kids are getting is not as effective as it was meant to be. Most kids get their final booster around age 11 or 12, and the outbreaks are happening to high-school aged kids – the vast majority of whom have an unpleasant week or two and then are absolutely fine. The CDC speculates that it is possible that the kids who have been vaccinated against whooping cough can harbor the bacteria in their system and when the vaccine efficacy wanes, as it is wont to do, it rears its ugly head and voila, kids get sick. Of course, they also speculate that it is possible that there are some unvaccinated kids out there who get it and pass it along. And they also speculate that the bacterium itself has mutated just enough to render the vaccine itself useless.

Like I said, no simple answers. Folks who like to believe that there is an anti-vaccine conspiracy often say that if everyone were vaccinated, there would be no virus/bacteria left to mutate and that is why everyone ought to just go get their kids every shot offered. Except that many of these shots are NOT SAFE for babies of a certain age, so there is no way to ensure that the virus/bacteria is gone forever. And there are some folks whose medical status is too fragile for them to get the vaccine, which means they have to weigh the odds of potentially dying from getting the shots against the potential that they might one day come in contact with the virus/bacteria in question. Again, no such thing as 100% vaccination and, thus, eradication.

In the days before vaccines, people did get sick and die from diseases like whooping cough, although generally that was because their health was not great for other reasons – malnutrition, immune disorders, age. More often than not, people got viral or bacterial infections and recovered from them and built natural immunity. Nursing mothers could pass this natural immunity on to their children in many cases, and there was very little need for a vaccine, much less a boost of immunity later in life.

All this is to say that I don’t think we can continue to place an inordinate amount of faith in the vaccination system. Yes, smallpox was eradicated by a vaccine. We all know the story. But one success story does not mean that this solution fits everything. And it also doesn’t mean we ought to stop asking questions about vaccine efficacy for other, different, less deadly diseases (READ: HPV). And it certainly doesn’t mean that we ought to feel free to vilify and radicalize people who are rightly concerned about their own children’s individual health.

Eve most certainly caught whooping cough from someone at school. Whether or not they were vaccinated against it means nothing to me. That kid came to school infectious, whether they knew it or not, coughed on Eve, or at the very least in her close vicinity, and the rest is history. Should I go on the school website and rail against the parents who send their kids to school with a fever or a nasty cough because it resulted in my kid getting really sick? I don’t think so. Generally, the only people who end up needing hospitalization for whooping cough are babies, the elderly, and those whose health is already compromised, so there was almost no chance she would suffer long-lasting effects from her illness. Going to school where there are other people – heck, going out in public, touching a door handle, using an ATM machine, breathing on an airplane – is putting you at risk for catching all sorts of things from other people who are either knowingly or unknowingly sick. We cannot ever hope to eradicate all possibility of getting sick from other people unless we choose to live in a bubble and that is a pretty sad, pretty fear-based existence. I’m not pissed off at the person who shared their whooping cough with Eve. I consider it part of the price of ‘doing business’ as they say. I’m only a little bit sad that Lola didn’t manage to catch it at the same time, if only so I know they’re both immune. Shhh, don’t tell her I said that.