In the past several days, I have seen more requests for people to “unfriend” and “unlike” pages on social media than ever before.

I have spoken with people who acknowledge that their loved ones voted for a different Presidential candidate than they did and roll their eyes, saying that they don’t get it.

I have seen calls for parts of the country to split off from the rest because of the deep philosophical divisions that showed up on Tuesday night, and I have listened and watched as groups form with the intent to “fight.” I heard one person say last night that she doesn’t talk to people who voted differently than her because “we can’t.”

We can’t afford to not talk about this.

It’s hard.

It is often painful.

It sometimes feels as though we are speaking different languages.

And we have to try.

The future of our country depends on it.

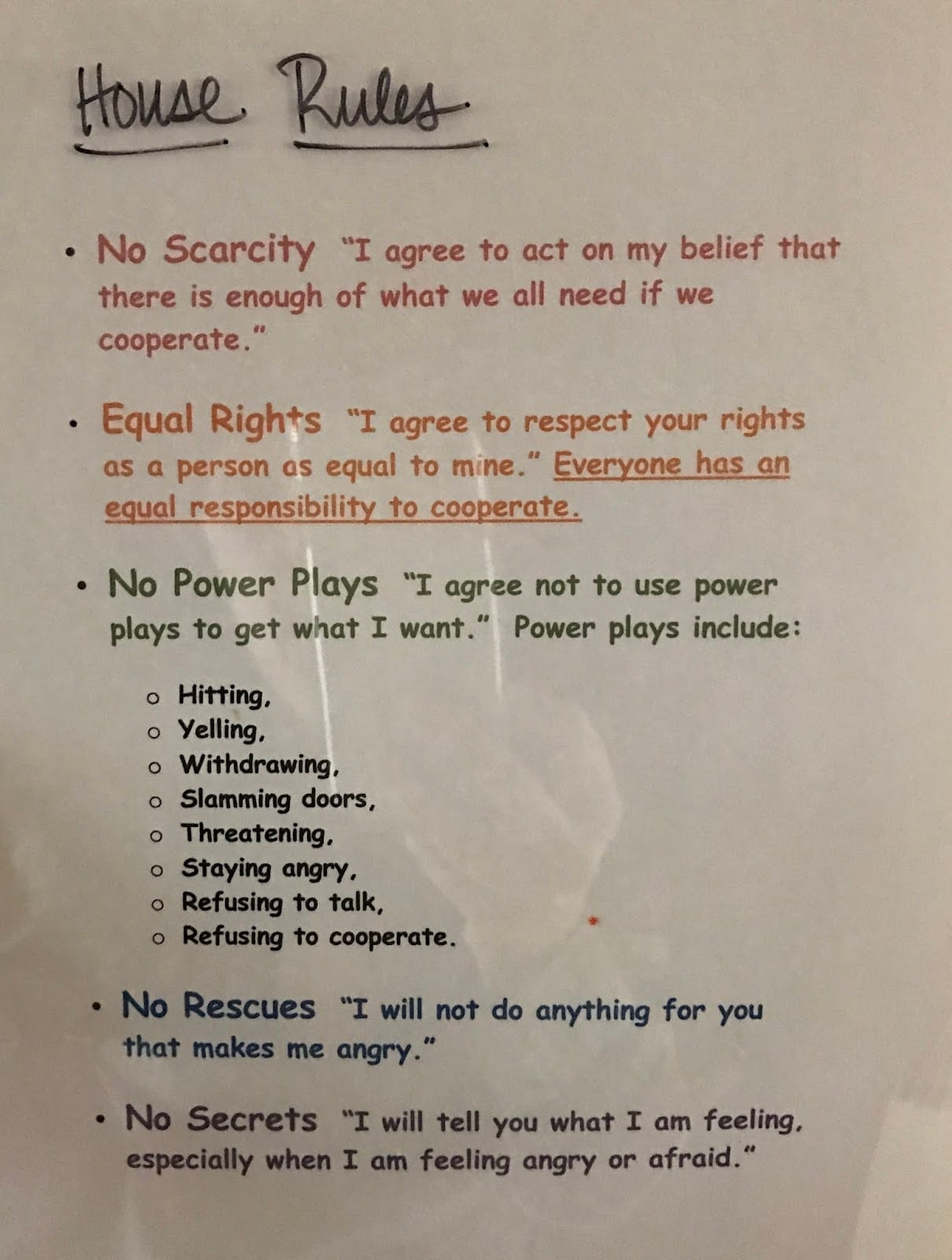

The first thing we can do is stop pretending that debate is conversation. In a debate, there are sides. There are factions with deep-seated beliefs and the goal is to show up and talk the other person under the table. The entire setup is predicated on the idea that this is a zero-sum game. That one side is “right” and the other is “wrong.” Debates are about power, they aren’t about common ground, and what the American people need right now is to find our common ground.

Instead of one-upping each other, we need to listen.

Instead of either/or, we need to start thinking in terms of yes/and.

When Lola headed out to take the bus with a couple of friends to the movies yesterday, I nearly had a panic attack. At some point, it occurred to me that I was sending my 14-year old daughter out with another young woman (who happens to be black) on to public transit and out into the world without an adult. Before Tuesday, I wouldn’t have given it a second thought. But in the days following the election, my Facebook feed was filled with stories of women and girls being harassed in public, people of color and Muslims attacked for simply being who they are, and I was gripped by fear. I hated the fact that I had to give her instructions as to how to behave on the bus – eyes up at all times, assess the situation constantly, if your gut tells you something isn’t right, scan the area for the nearest trustworthy adult and have an exit strategy that puts you in a safe place. I tried to do it as calmly as I could without scaring her, but still letting her know that she needed to heed my warning.

I am keenly aware of the daily fear that accompanies being a woman in this country. I am also aware of what many of my friends who are people of color go through on a daily basis and I think I understand their fears. I have heard and acknowledge the fears of those who are immigrants, refugees, and people who do not identify as Christian. I also feel as though I understand the concerns of folks who are part of the LGBTQ community.

And…

Yesterday, I had a very interesting exchange on Facebook with someone who supported Donald Trump’s presidential bid. He wrote that he wanted us to all stop fighting and start working to make this country great for “our kids,” and I inquired whether he meant all kids – black and brown kids, immigrant kids, gay and transgendered kids, and Muslim kids. What ensued was more than 30 minutes of back and forth clarification, peeling layers to really understand what he meant by making our country great and if it was inclusive of all of us. What I learned was that he doesn’t care a whit about reversing Roe v. Wade or marriage equality. He isn’t interested in deporting anyone and he believes that the Bill of Rights was written to include every single one of us, regardless of what we look like or where we worship or who we love. His reasons for voting the way he did had nothing to do with racism, xenophobia, homophobia or sexism.

In my quest to understand, I had to refrain from lumping him into the box that is so handy and makes it easy to jump right back in to that zero-sum game of Wrong and Right. Goodness knows, I didn’t agree with Hillary Clinton on everything she said. In fact, I vehemently disagree with her on several issues, and I know that I wouldn’t want to be characterized as someone who is in full support of her positions on military spending or energy policy. Because of that, it is my responsibility to treat others the same way. I can’t make a blanket statement that every single person who voted for Trump is racist, misogynistic or sexist. They may well have voted for him despite that.

And…

The fears of folks Trump has alienated and denigrated are real.

They have every right to have their feelings validated and fight to keep their personal freedoms.

And…

The fears of folks who don’t live in urban areas where the economy is rebounding, where opportunities exist for job training and social programs are just as real. Those folks who have struggled to put food on the table for their kids, whose schools have been taken over by the state because they have failed to meet standards for years, who have been farmers and miners for generations and still want to be, but those jobs are going away or getting harder to do without the support of the government? Their feelings are just as real. Their fears are just as existential.

They have every right to fight for someone they hope can pay attention to their plight, too.

Just because I haven’t lived those fears doesn’t mean they aren’t real. They just don’t show up on my radar. Like the fears of women and immigrants and minorities don’t show up on the radar of folks who haven’t lived that reality.

We can continue to try and convince each other that the things that show up on our personal radars are more important than the things that show up on someone else’s if we want to. We may gather bigger numbers next time and “win” elections. But we won’t have addressed the underlying issues that are driving the divide and we will continue the wild swing of this pendulum that throws our country into chaos every few years. The only way to slow it down is to learn about each other, to set aside what we think we know and listen to what others live with. Unfriending each other or voting to split states off from the Union might make us feel safer, but it only deepens the divide. And it won’t make the other side go away. It certainly won’t make them change their minds. It is the equivalent of a parent kicking their teenage daughter out of the house because she is pregnant. It doesn’t make her any less pregnant, it just leaves her with fewer supports and it means you don’t have to look at her anymore when you come downstairs for breakfast. We have to face this with compassion and a genuine desire to find commonality or we will continue to break apart even more. I truly believe that the people of this country have more in common with each other than we know. It is in our own best interest to find those goals we all share and begin talking to one another because it appears that there are some folks in power who are more interested in being Right than they are in being part of something real and honest and human.