Human nervous system spectrum

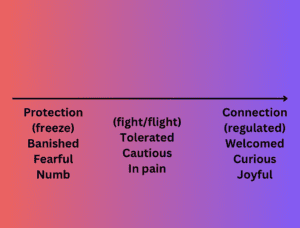

If you know me, you have very likely heard me say the following: “urgency never equals safety.” From a strictly physiological point of view, when we are in a space of urgency, while we may be technically safe from harm, our nervous system is in fight/flight/freeze – it is activated and pushing us to resolve the situation as soon as possible. The challenge with this is that our bodies aren’t always able to discern when urgency is warranted and when it’s manufactured. And in general, decisions that are made when we are in fight/flight that aren’t strictly about our safety or survival are not decisions that come from the part of our brain that is tasked with self-awareness, critical thinking, and creative problem solving.

Manufacturing urgency is about manipulation. It is about trying to convince someone to make a choice quickly, or else….! Often, the “or else” part isn’t clearly defined, and when the human brain is left to fill in the blanks, and our nervous system is activated, we generally complete the story with the worst-case scenario, thereby allowing ourselves to be manipulated into doing the thing we’re told will avert disaster.

This is weaponized in so many ways – from sales that end quickly, where we get emails or text messages saying we only have a “limited time” to pleas for donations “before the deadline,” to workplaces prioritizing folks who can “work in a fast-paced environment,” and more. Even the word “deadline” is manipulative because, in general, nobody is going to die if you don’t get that report in by 5pm or give just $20. (It doesn’t mean there aren’t consequences, but often those are manufactured as well).

The human body is masterful and miraculous. It is not designed to be in a steady state at all times, but to do the things that will bring us back into balance when things are out of whack. It is why we sweat when we’re too hot or shiver when we are too cold. It is why, when we are afraid, our hearts begin to pump faster and adrenaline is released into our bloodstream to prime us to either run away or fight. We are supposed to move through phases of calm, agitation, and even “freeze” over and over again. But our Western, capitalist culture has prioritized and celebrated the folks who live in a fight/flight state, who stay activated and are willing to make snap decisions (if I had a dime for every time I heard the phrase, “ask for forgiveness, not for permission,” I would own a yacht), and who incite others to live in that same space.

The folks who are either in freeze, paralyzed and overwhelmed by the pace and demands are sidelined, mocked, and seen as not tough enough. The ones who are calm and regulated and want to slow down and make considered decisions from a place of creativity are often seen as barriers to getting things done. But the sad truth is that the more we manufacture urgency to keep folks in fight/flight, the more we burn people out. That pace is not sustainable in any way, shape, or form, and while your boss might want you to churn out work to manufactured deadlines over and over again, or react to unexpected situations with a scarcity lens, those things are not conducive to health, well-being, and longevity, for you or your organization.

I spent several years working as a medical/surgical assistant and I’ve seen my share of unanticipated, bloody, frightening situations (many of them complete with flashing lights and audible alarms). At first, those things catapulted me into fight/flight for an instant, and then, thanks to my training, I was able to find calm and make decisions to avert the crisis with a team of others who were also well-trained. While we like to portray one person as the ‘take charge’ type/hero – slapping the hysterical person so they stop screaming or ordering people around who are frozen in fear – it is my experience that that is rarely the case. Having a team of folks who are able to calm their own nerves and work cooperatively with others to solve the problem at hand is incredibly important, because when we are in fight/flight/freeze, the portion of our brain that processes language is severely compromised, and we often don’t have a full understanding of the complexity of any situation.

As a parenting coach and a non-profit organizational relationship consultant, I am often in the unique position of noticing when someone in a family or team has adapted to being in fight/flight so well that they seem like the most consistently competent person in the room. They take charge, often assume responsibilities that aren’t really theirs, and send the message that they are either the only one who is willing to do it or the one on whom this was dumped because they are the most competent. Again, rarely, if ever, in families and organizations I work with, is it the case that things are truly make-or-break, but the urgency is manufactured and weaponized by the person who is in fight/flight (and often not in a conscious way at all) in order to manipulate others into quickly making a decision so they will feel better.

Making deliberate, intentional, collaborative decisions requires us to stay in discomfort until we are able to recognize that we are safe and understand what the challenges are without blowing them out of proportion and reacting from a place of fear or scarcity. When we can get our language processing back online and work together with a true assessment of the situation, we are able to find creative solutions and/or determine that this problem we were trying to solve wasn’t really a problem after all. One of my other favorite sayings is, “when you’re holding a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” Getting out of nervous system activation is an opportunity to put the hammer down and discern whether or not this obstacle in our way truly needs to be smashed, or if we can simply walk around it and keep moving forward.

We have been so conditioned to think that quick, decisive actions are a sign of strength that many of us are loathe to slow down and take a beat before making a choice, but it is important to remember that our nervous systems “read” each other and when I get in an unexpected situation and see someone who isn’t rattled, I am much more likely to want to listen to them than the loudest person in the room who is clearly carrying a hammer. If I have a choice, I’d rather have my nervous system influenced by the person who is calm than the one who wants to draw me into agitation just to get their needs met.